28th April 2021

Out Now: Stuart Hall's Selected Writings

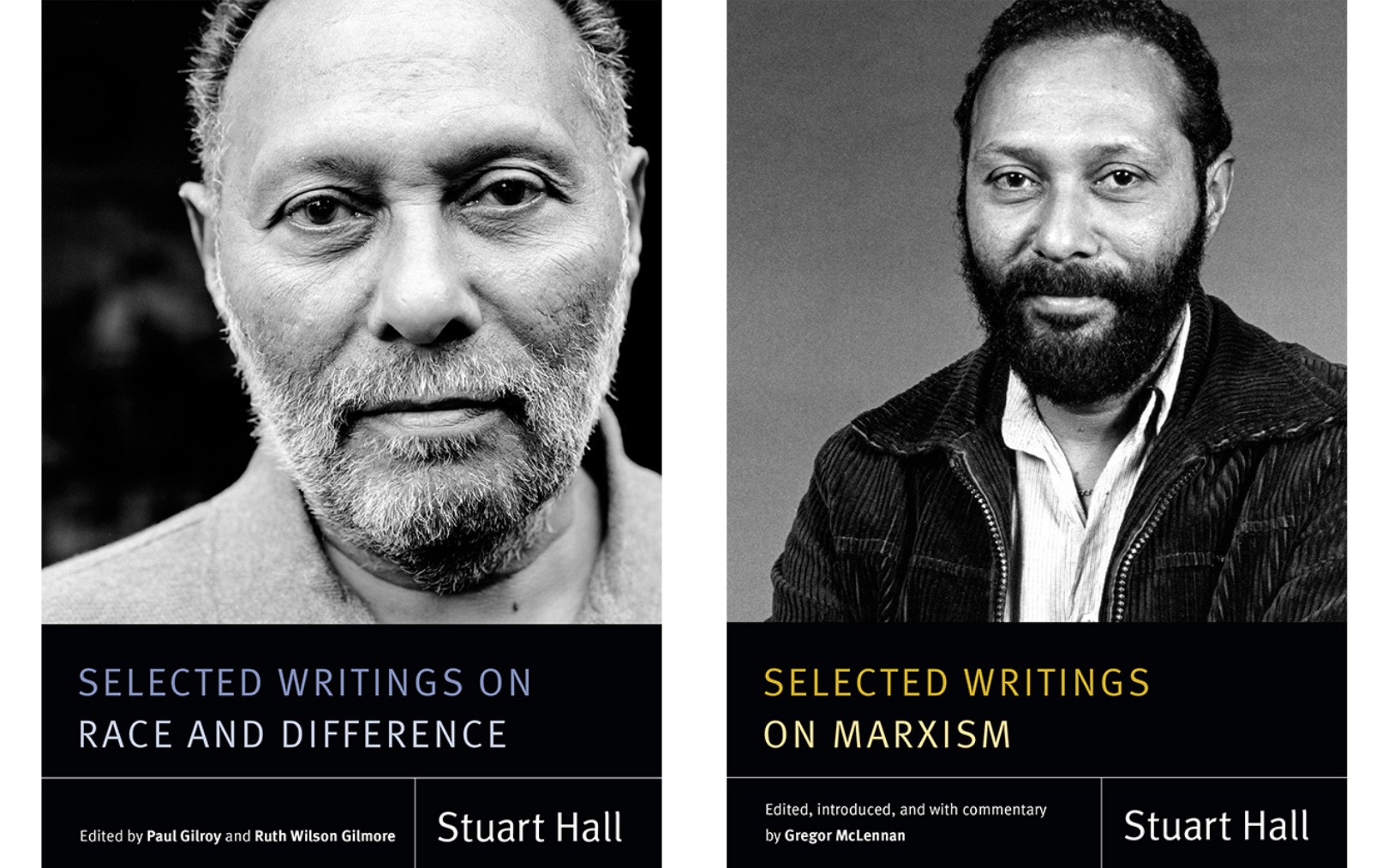

We are pleased to announce the release of two new Stuart Hall titles published by Duke University Press: ‘Selected Writings on Marxism’ edited by Gregor McLennan, and ‘Selected Writings on Race and Difference’ edited by Paul Gilroy and Ruth Wilson Gilmore.

Purchase your copy today from CAP (Combined Academic Publishers) or if you are based in North, South, and Central America then you can order direct from Duke University Press.

Related

"...intellectuals whose indispensable work one returns to over and over again."

"...intellectuals whose indispensable work one returns to over and over again."

21st July 2021 / Article

The Impossibility of the Black Intellectual

By: Sindre Bangstad

...intellectuals whose indispensable work one returns to over and over again.

"...intellectuals whose indispensable work one returns to over and over again."

Stuart Hall, the British-Jamaican cultural theorist, would have been open to and pragmatic about the ideas of the younger generations of anti-racists now in the making.

There are some scholars and intellectuals whose indispensable work one returns to over and over again. For me, as for so many others, it is the late Cultural Studies’ founding father, professor Stuart Hall (1932-2014). For though much of Hall’s rich oeuvre came in response to concerns in the context of Black and anti-racist struggles in his adopted homeland of the UK in a period spanning from the 1950s until his death in 2014, it still feels remarkably prescient and relevant to the present conjuncture.

Read the full article on Africa is A Country.4th May 2022

New Soundscape by Artist Trevor Mathison at Highgate Cemetery

The Stuart Hall Foundation is thrilled to announce The Conversation Continues: We Are Still Listening, a newly commissioned audio-based artwork...

Stay connected

Sign up to our newsletter for the latest news, events and opportunities:

Share this