Read

The Contextualising Climate Crisis Series

18th January 2022 / Video

Frontlines: Land and the Climate Crisis with Abeer Butmeh, Dr Hamza Hamouchene and Sam Siva

18th January 2022 / Video

Frontlines: Land and the Climate Crisis with Abeer Butmeh, Dr Hamza Hamouchene and Sam Siva

Land both contributes and is affected by climate change. It is the frontlines of the climate crisis where livelihoods, resources and inherited...

18th January 2022 / Video

Frontlines: Land and the Climate Crisis with Abeer Butmeh, Dr Hamza Hamouchene and Sam Siva

Land both contributes and is affected by climate change. It is the frontlines of the climate crisis where livelihoods, resources and inherited knowledge are fought for against industrial extraction, the militarism of imperial ventures, and colonialism’s erasure of indigenous epistemologies. This conversation asks how land is central to efforts to both deepen and circumvent the crisis?

For this #ReconstructionWork event the Stuart Hall Foundation welcomes three leading climate activists: Abeer M. Butmeh , Dr Hamza Hamouchene and Sam Siva to share their experiences, imaginings and reflections around land and the climate crisis.

Part of our Contextualising Climate Crisis series and our #ReconstructionWork online conversation series.

Supported by Arts Council England

"we must empower communities on the frontlines of climate breakdown"

"we must empower communities on the frontlines of climate breakdown"

10th January 2022 / Article

The End of the World is Never the End of Everything

By: Arwa Aburawa

we must empower communities on the frontlines of climate breakdown

"we must empower communities on the frontlines of climate breakdown"

“The climate crisis wasn’t solely caused by empowering an exploitative logic, it was caused by disempowering the very communities which could counter this logic.”

The concept of ‘Anthropocene’ argues that humans (Anthropos) are altering the earth on such a scale that we have left the previous geological epoch (the Holocene) and entered a new one. The pervading narrative around the climate crisis, this age of Anthropocene, is that all humans have contributed to creating a crisis which we must now come together to solve. Blaming all of humanity might seem benign but it’s important to emphasise that we have not all played an equal part in bringing forth this crisis. As Jairus Victor Grove explains, this “apocalyptic era has been unequally created by a minority bent on the accumulation of wealth and a self-interested political order” that affirms the humanity of some and denies the humanity of others.[1] The Jamaican writer and cultural theorist Sylvia Wynter explains that she will not miss the concept of the anthropos “because, among so many things, she was never considered human to begin with.”[2]

The climate crisis was caused by a European project, one in which slavery, the genocide of indigenous peoples, the globalisation of an insatiable extractive economic model, species loss, ecological destruction and climate change are all part of the same global ordering.[3] In other words, the same logic that enslaved human beings and robbed people of their resources under colonialism continues to forcibly extract labor through privatised prisons while pillaging natural resources for profit from a planet in crisis. This exploitative and extractive economic model that has historically emanated from Europe has been with us for centuries and continues to cause unspeakable violence. The climate crisis we are witnessing today can be read as the accumulation of all the death and destruction that brought the modern world to bear.

The need to contextualise the climate crisis isn’t about assigning blame, it’s about being clear about who we ought to be listening to in our search for solutions. The climate crisis wasn’t solely caused by empowering an exploitative logic, it was caused by disempowering the very communities which could counter this logic. This is what we must redress.

In her book A Billion Anthropocenes or None, Kathryn Yusoff states:

“If the Anthropocene proclaims a sudden concern with the exposure of environmental harm to liberal communities, it does so in the wake of histories in which these harms have been knowingly exported to Black and brown communities under the rubric of civilisation, progress, modernisation and capitalism. The Anthropocene might seem to offer a dystopic future that laments the end of the world, but imperialism and ongoing (settler) colonialism have been ending worlds for as long as they have been in existence.”5

When Black, brown and indigenous communities suffered, when their worlds ended, it was deemed an acceptable price to pay for a version of progress that continues to rely on the destruction of environments, livelihoods and communities. As we face this unprecedented crisis, we must empower communities on the frontlines of climate breakdown, we have to listen to colonised people because this isn’t the first time they are contemplating the apocalypse. We have faced it before – and time and time again our ancestors found ways for us to survive. I count myself as one of the survivors. We, the descendants of Black, brown and indigenous communities, have survived by finding new ways to live under a global system which sees the end of our lives and ecologies – our literal genocide – as a sign of our weakness and its right to dominate and oppress us.

We can survive this crisis because we’ve survived other endings of worlds through a multitude of small ways: holding onto values, traditions, arts, languages and ways of connecting and relating with one another which are deemed primitive, backward and antithetical to ‘progress’. We hold onto our faith, our families, our food and our lands because our existence depends on our resistance. Solving the climate crisis doesn’t need a big overarching solution. What we need is to listen to the millions of answers that are offered every single day by colonised communities who have found and continue to find intergenerational ways to survive the ending of worlds. As Grove reminds us, “the end of the world is never the end of everything”.

This piece explores themes that Arwa Aburawa has been working on for an archival film commissioned by the Liverpool Arab Arts Festival 2021.

Footnotes1 Jairus Victor Grove, Savage Ecology, War and Geopolitics at The End Of the World, 2019, pg49

2 Jairus Victor Grove, Savage Ecology, War and Geopolitics at The End Of the World, 2019, pg11

3 Jairus Victor Grove, Savage Ecology, War and Geopolitics at The End Of the World, 2019, pg38

4 United in Struggle by Nick Estes, Ruth Wilson Gilmore and Christopher Loperena, August 2021, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10714839.2021.1961444

5 A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None by Kathryn Yusoff, 2018, preface xiii.

_

Arwa Aburawa is a London-based documentary filmmaker and writer with an interest in the environment and race. She is also co-founder of Other Cinemas, a community project which shares the films and stories of Black and non-white people in spaces and ways which aren’t alienating to these communities._

This piece was commissioned as part of the Contextualising Climate Crisis series.

"We find ourselves at the back of a decade of broken promises"

"We find ourselves at the back of a decade of broken promises"

14th December 2021 / Article

Decolonial Methodologies

By: Ashish Ghadiali

We find ourselves at the back of a decade of broken promises

"We find ourselves at the back of a decade of broken promises"

Widely derided as a “talking shop” that failed to deliver on the climate action we need, the pageant around COP26 – the UN’s 26th “Conference of the Parties” that took place in Glasgow in December – pointed towards a deeper systemic malaise that’s emblematic of our times.

We find ourselves at the back of a decade of broken promises and inaction by international governments and transnational corporations that has seen the earth’s atmospheric temperatures rise to 1.2˚C above pre-industrial levels, driving us ever closer to the guardrail of 1.5˚C.

“1.5 to stay alive” was the slogan of campaigners from the world’s most climate vulnerable countries at COP14 in Copenhagen in 2009. The target was enshrined in the Paris Agreement at COP21 in 2015, then centred by leading climate scientists in the IPCC’s 2018 report as a crucial threshold not to be breached for the preservation of water, food, housing and biodiversity systems around the world.

Earlier this year, a blueprint for what it would take to achieve 1.5˚C came from the unlikely quarter of the International Energy Agency [IEA], highlighting the urgency of bold immediate term (2025) and short-term (2030) commitments to decarbonisation.

Yet the UK government, president of COP26, approached the moment focused on long-term goals of achieving Net Zero by 2050 and based on questionable approaches including carbon-offsetting schemes that can only deepen existing inequalities of power and productivity and on speculative technological solutions that to-date remain unproven.

The strategy represented a failure of imagination of epic proportions, reflected too in questions of resource allocation where G7 leaders, including self-proclaimed climate champion Joe Biden, attempted to spin a victory out of plans to come good on a 12-year old (broken) promise to commit $100 billion a year in climate finance.

Given that during this past decade of rising global temperatures, with an increased frequency of extreme weather events, costs of loss and damage alone have now risen to in excess of $150 billion a year, the proposal that was on the table amounted to little more than sign-off on a deficit that climate breakdown runs deep through the global economy. (Though even on this they failed to deliver.)

So here’s the reality check. Based on existing rates of carbon emissions, as corroborated by the most recent report of the IPCC, we will breach 1.5˚C within a decade – driving food scarcity, conflict, forced migration and continued economic breakdown around the world.

These effects will incur costs that will escalate and will be felt most by future generations (our children’s children) and by communities living on the frontlines of climate breakdown who are, above all, black and brown people living in the global south.

The failure to adequately plan and mitigate against those costs, alongside the challenge of decarbonisation, needs to be read now as a failure of governance that will perpetuate and exacerbate the inequalities of a 500-year old history of empire and racial capitalism.

It’s this deeper system, of empire’s inequality, that lies at the roots of both COP26 in all its failures, and of the 21st century’s environmental crisis itself. It now demands its transformation.

_

Ashish Ghadiali is a filmmaker and activist who organises with the climate justice collective Wretched of the Earth. He is a member of the co-ordinating committee of the COP26 civil society coalition and a commissioning editor at Lawrence and Wishart Books where he’s developing a new Soundings imprint, to be launched with a slate of books on Race and Ecology in 2022. He was formerly Race Editor, then Co-Editor of Red Pepper magazine (2017-2020) and part of the team that set up the Freedom Theatre in Jenin Refugee Camp (in 2006).

Ashish’s 2016 feature documentary, The Confession, explored the geopolitical arcs of the War on Terror through the testimony of former Guantanamo detainee Moazzam Begg. The film was described by The Guardian as “a documentary of great clarity and gravitas” and by Sight and Sound as “an interrogation of the very nature of truth-telling, freedom and responsibility”. Ashish is currently developing new projects for film and TV with BBC Studios and BBC Films and is a regular contributor to The Observer New Review.

_

This piece was commissioned as part of the Contextualising Climate Crisis series.

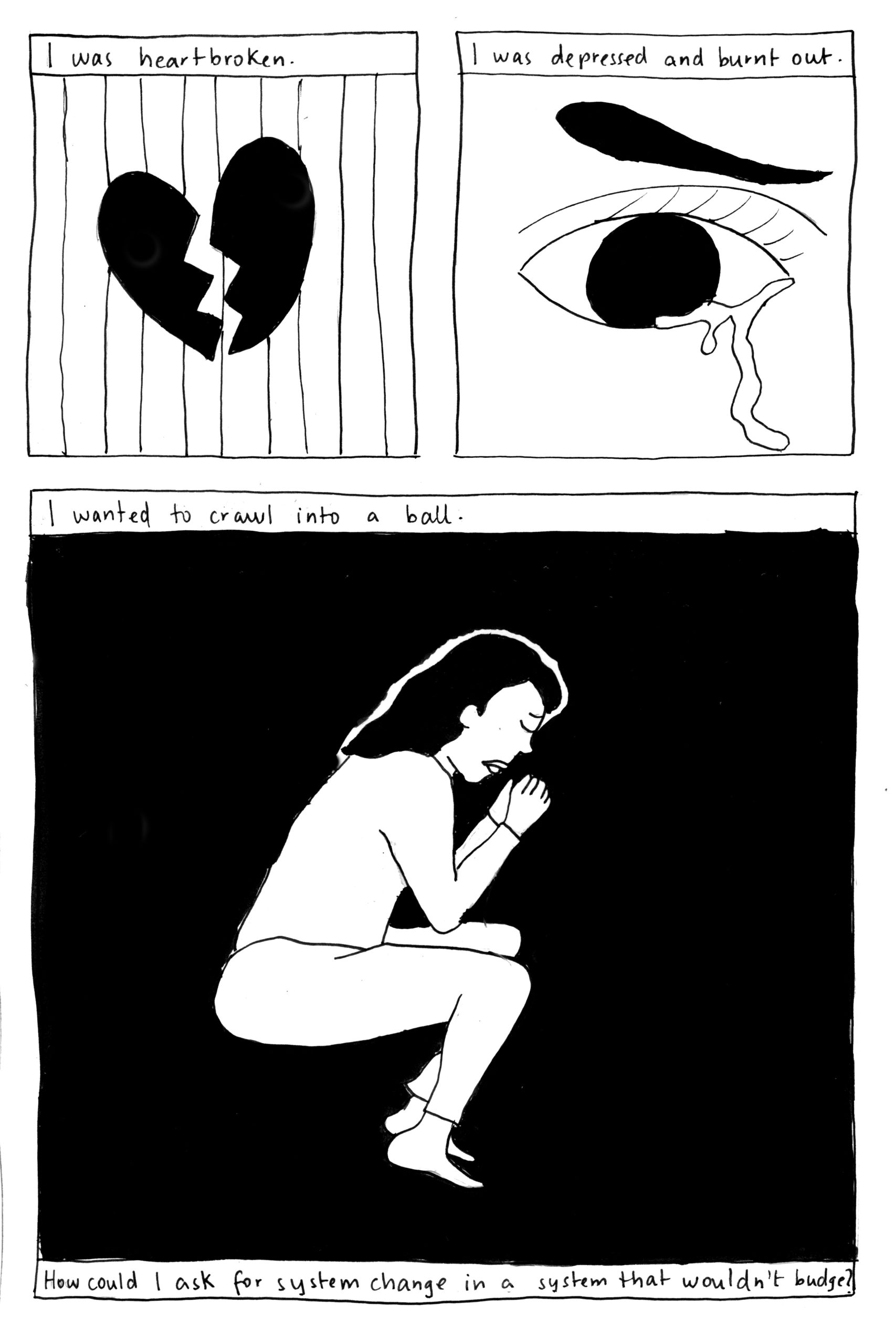

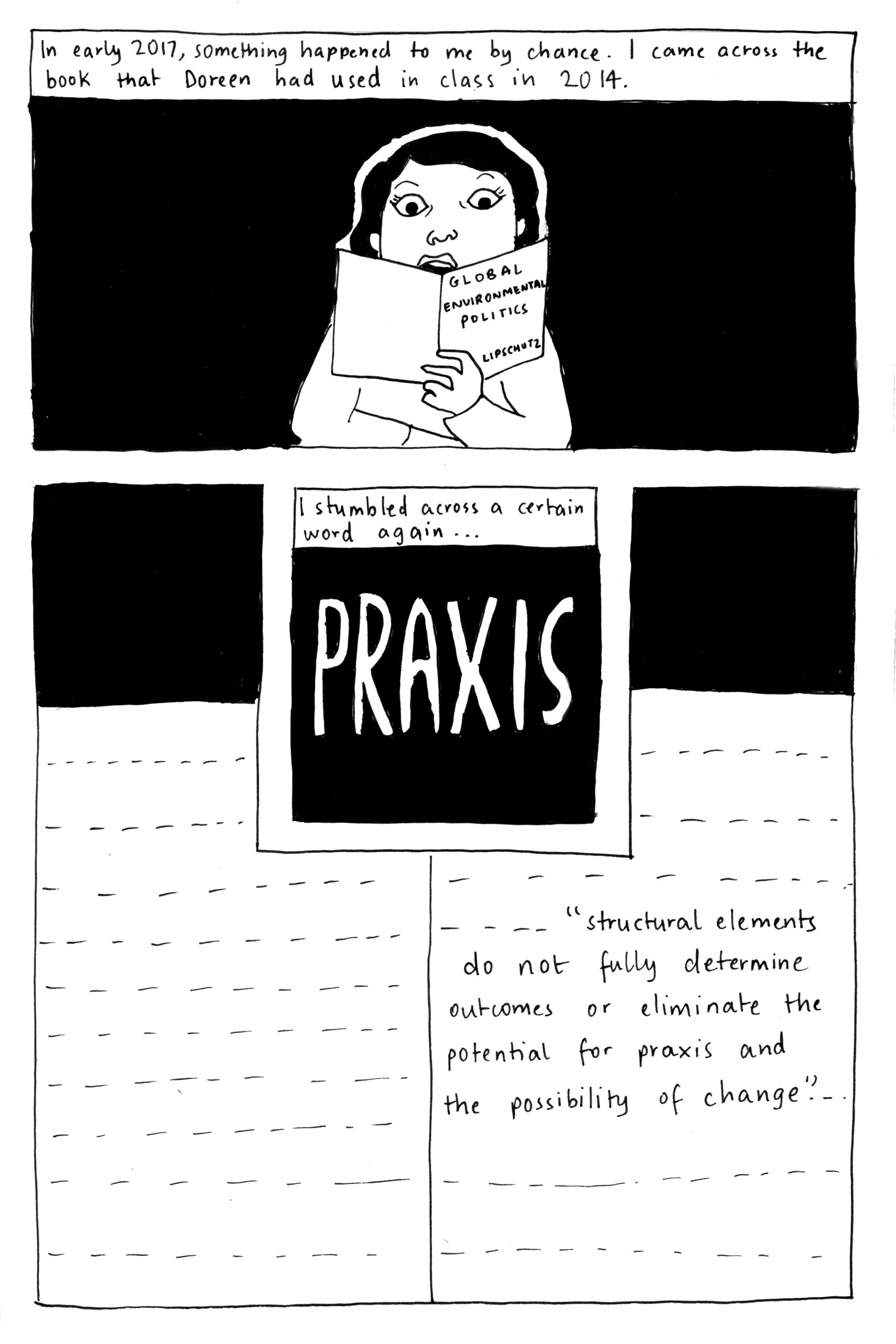

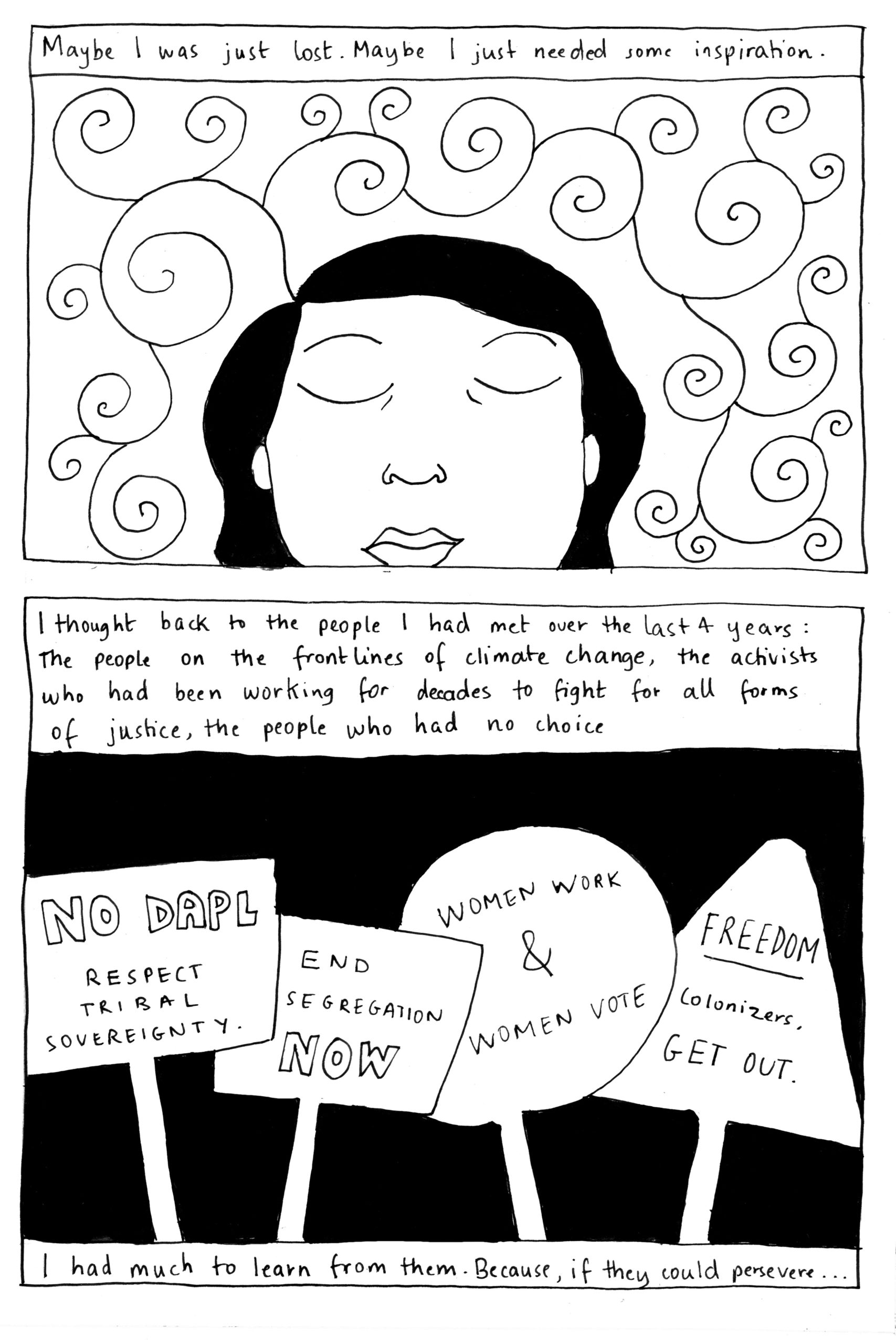

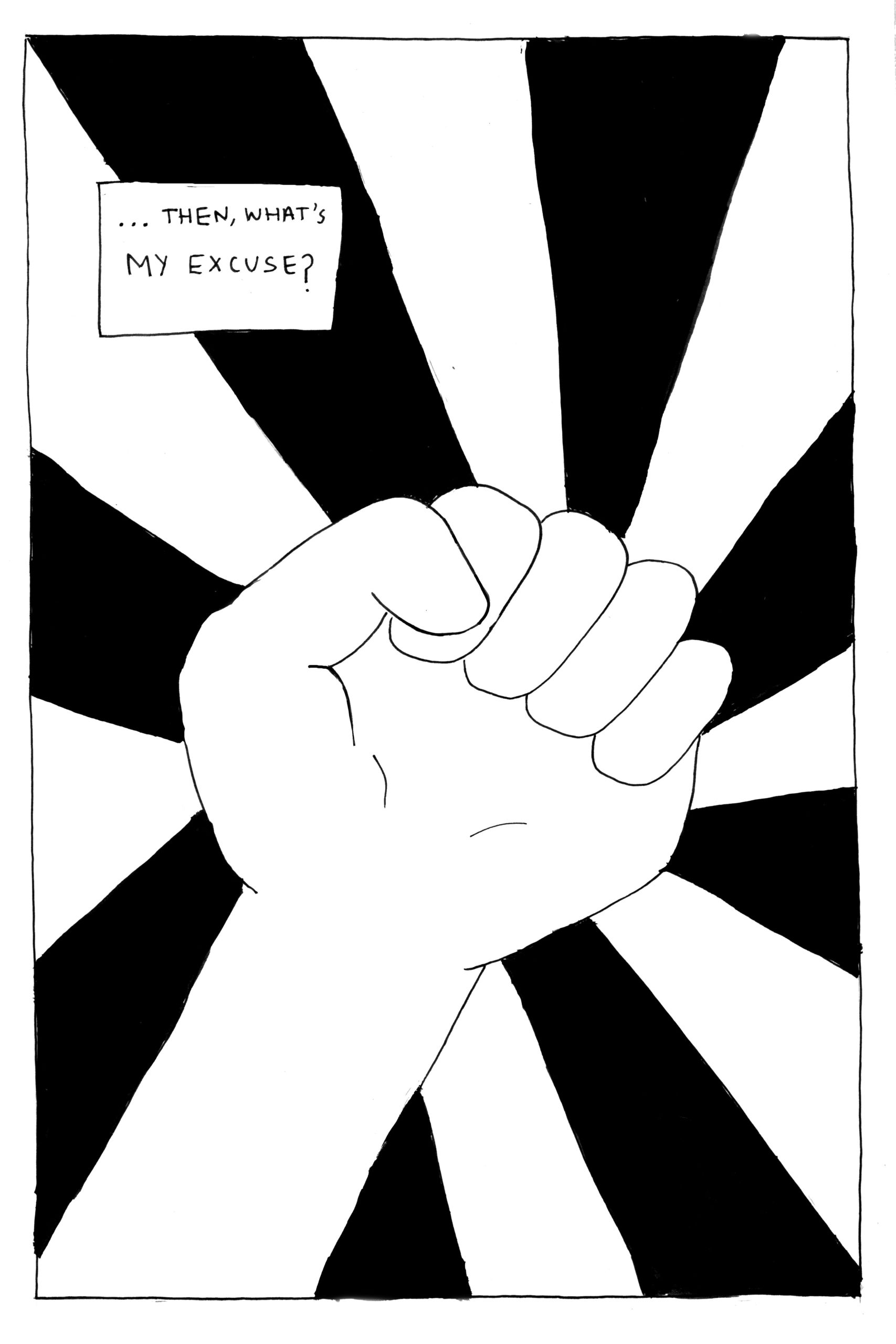

"Environmental politics must involve praxis."

"Environmental politics must involve praxis."

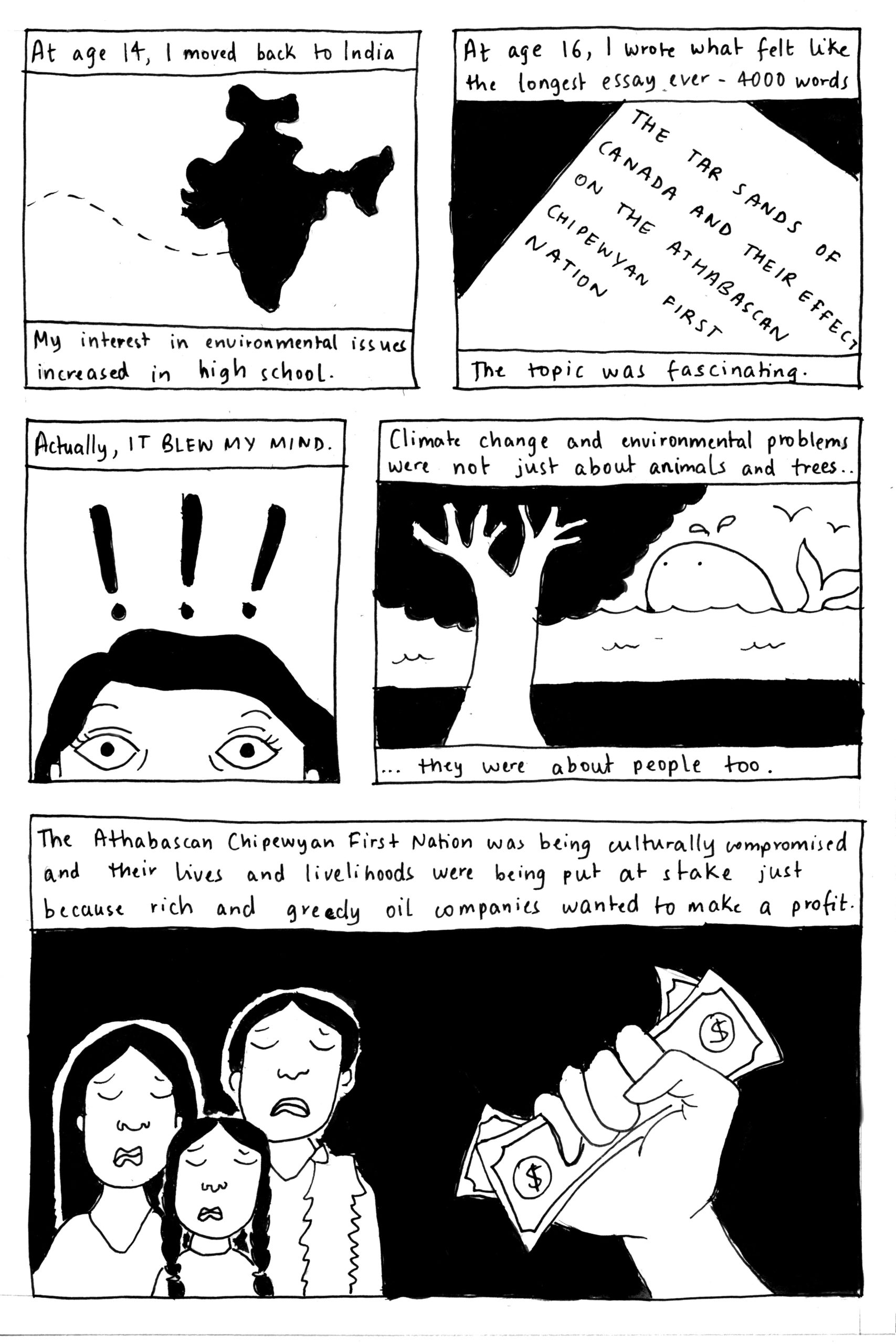

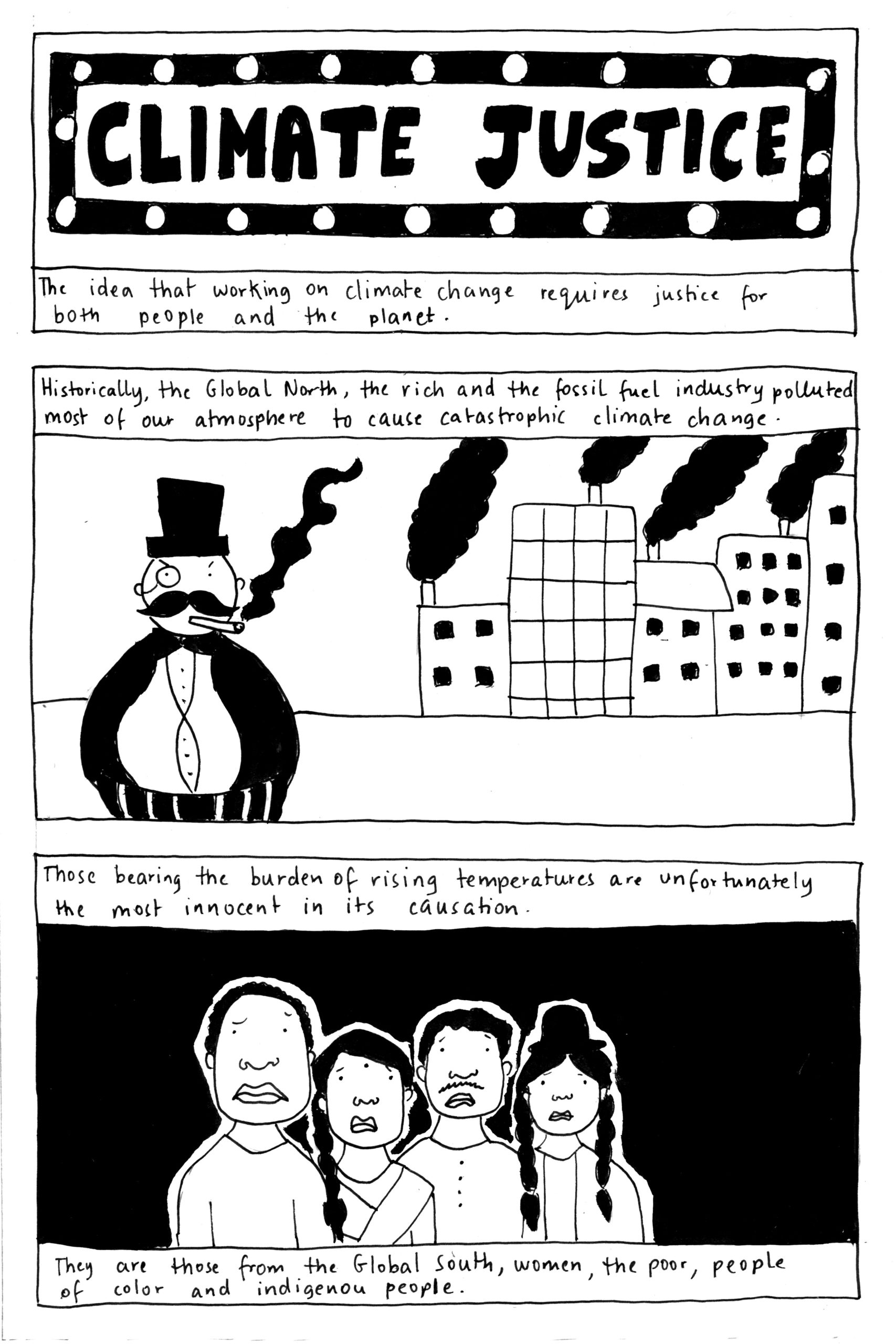

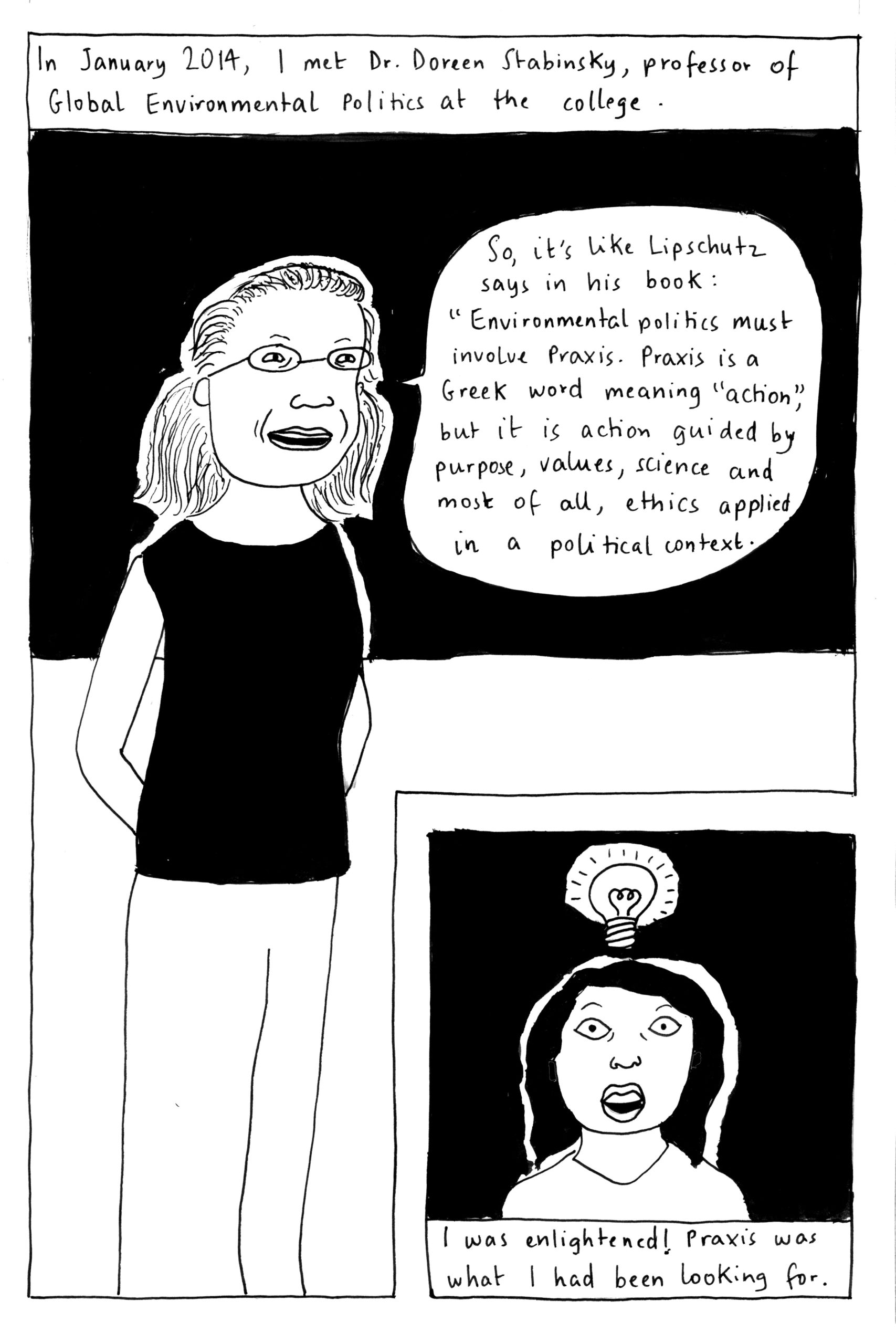

1st December 2021 / Article

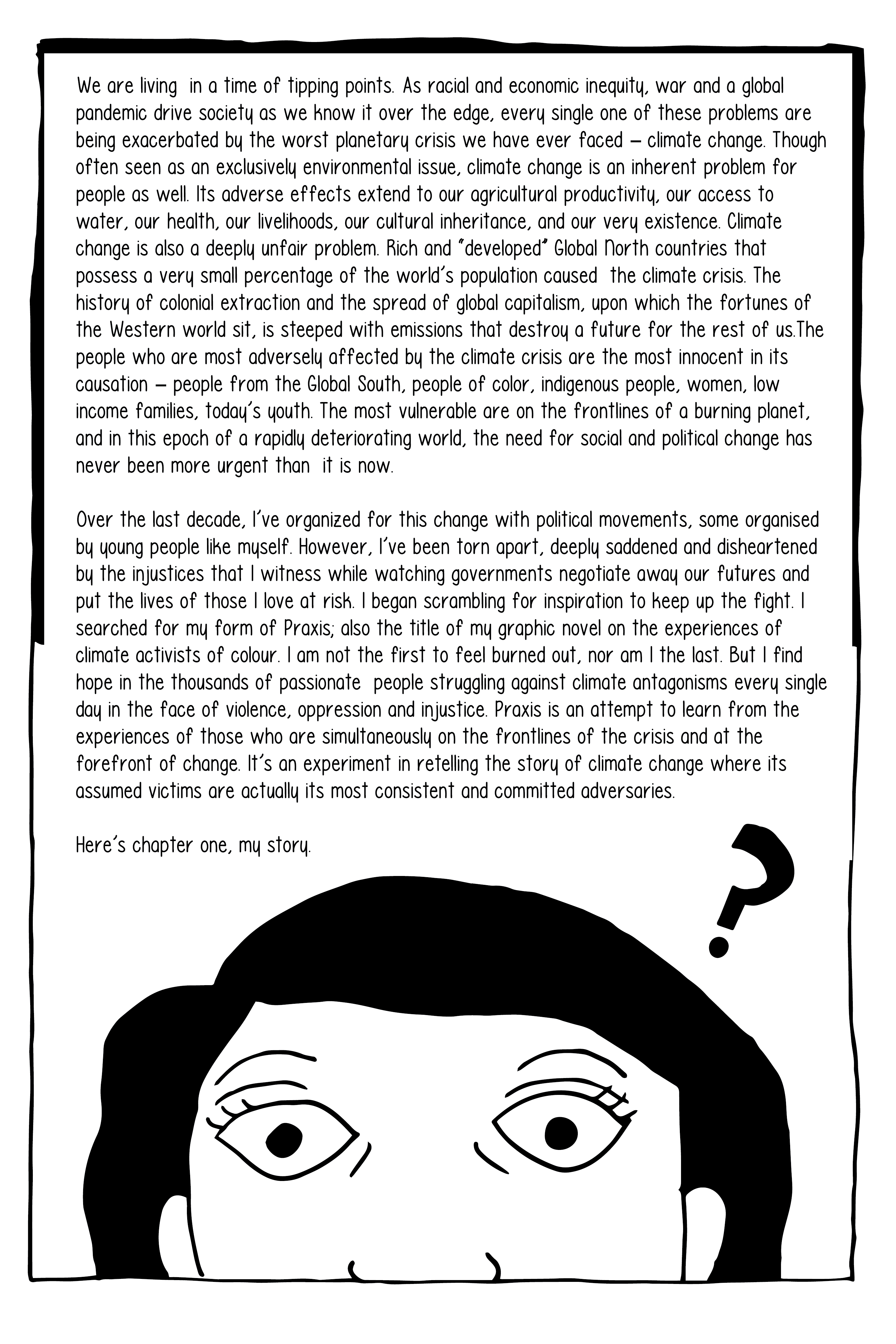

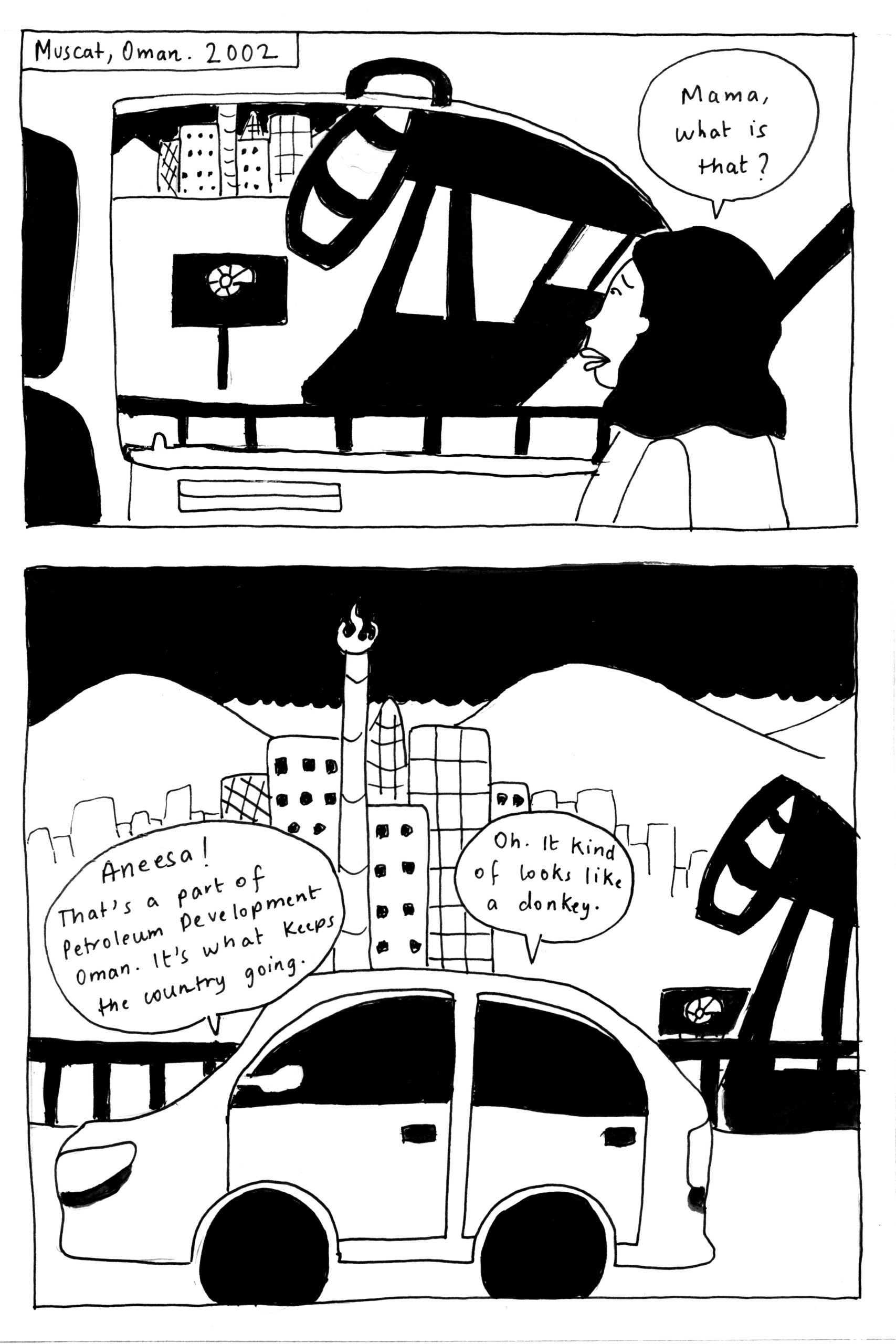

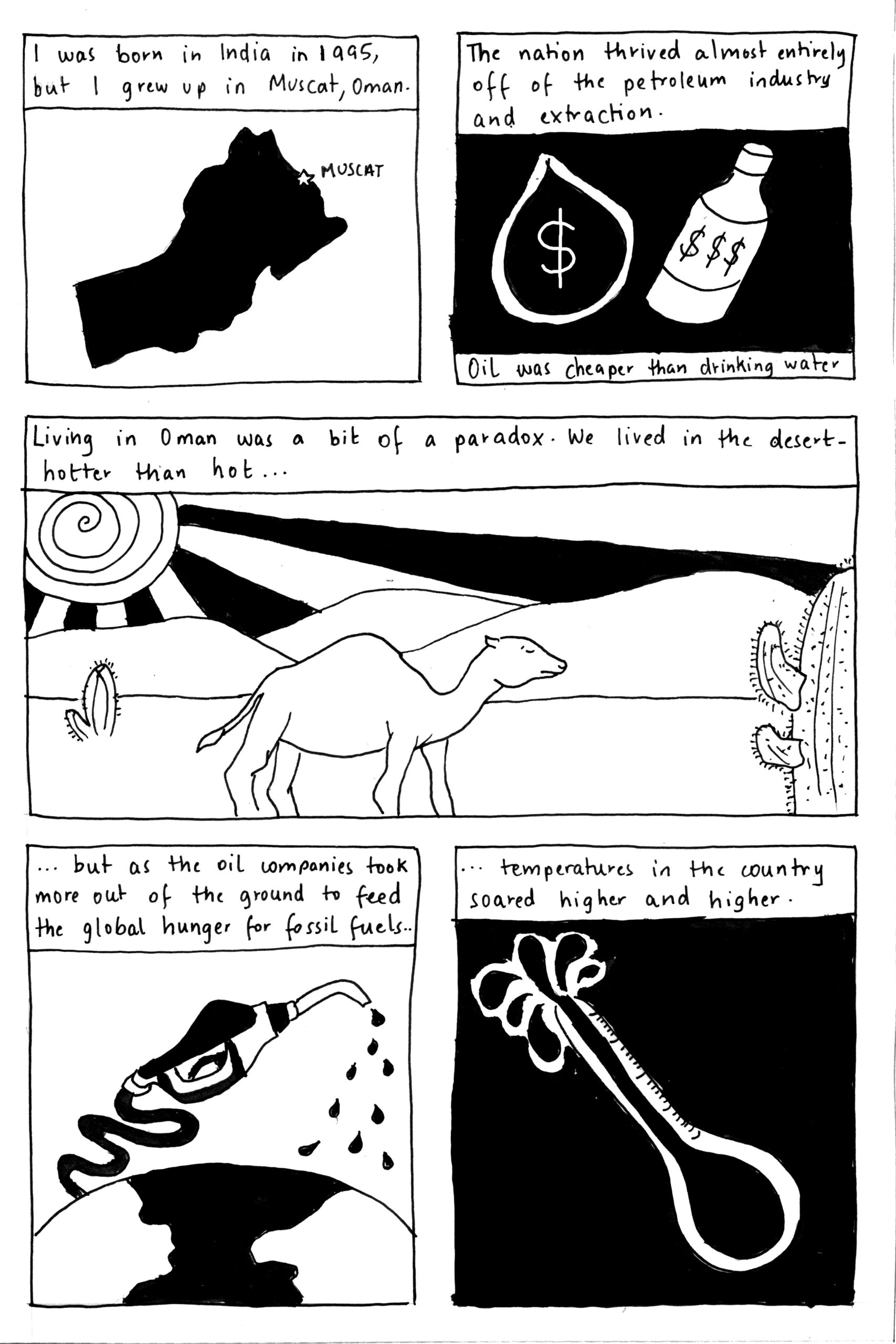

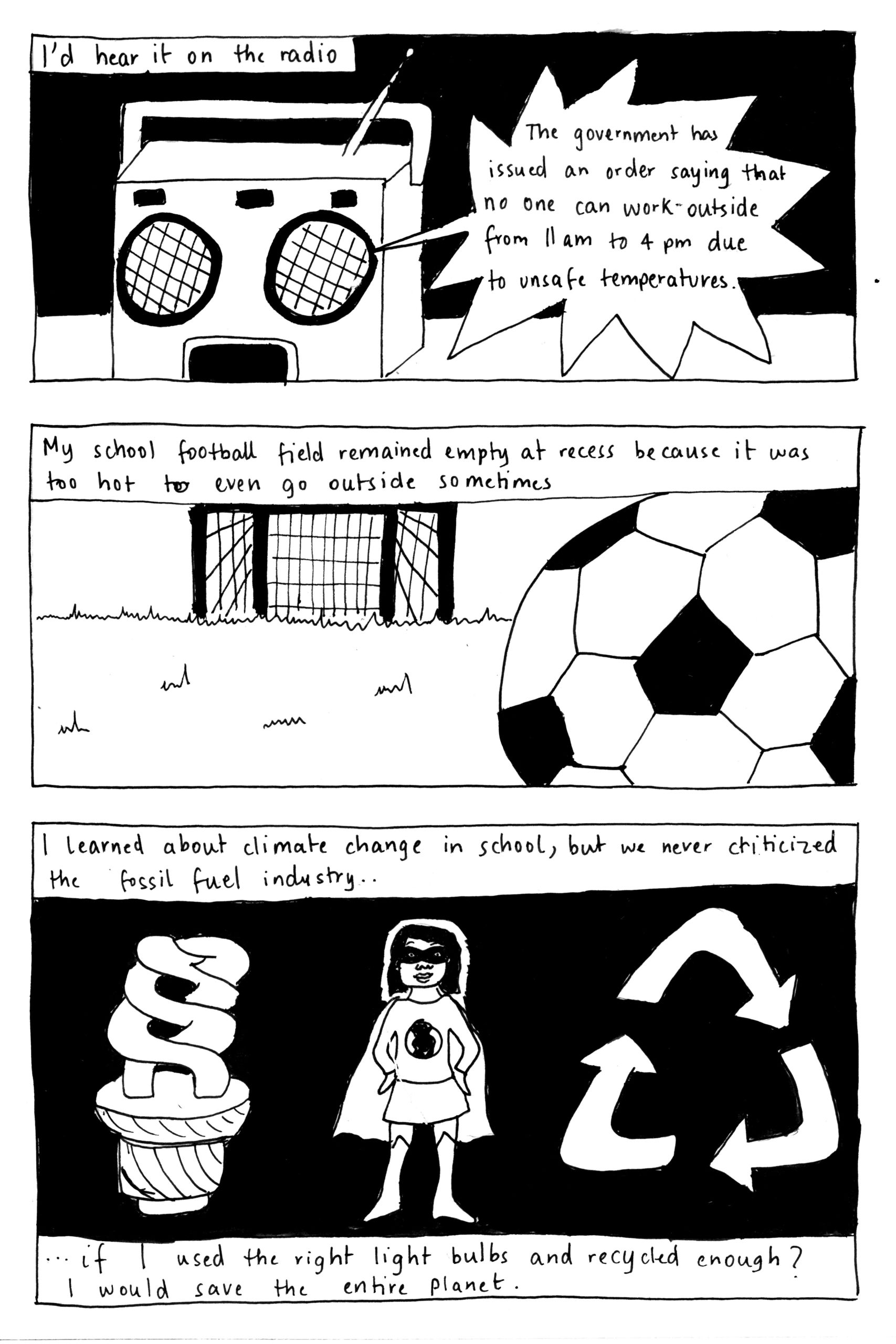

Praxis: A Graphic Novel

By: Aneesa Khan

Environmental politics must involve praxis.

"Environmental politics must involve praxis."

Born in South India and raised in Oman, Aneesa Khan joined the climate justice movement as a student with a passion for environmental law and creative storytelling. She started by organising for climate reparations at the UN climate talks where she worked to make sure the voices of black, brown, indigenous, and Global South youth were heard loud and clear over those of polluting industries. She has multiple years experience of organising in the US and globally as an activist with Friends of the Earth International, The Wilderness Society, and most recently, SustainUS – a youth-led climate justice organisation where she served as the Executive Director. She currently works as the Communications Officer for Oil Change International to expose the true cost of fossil fuels on people and the planet. She specialises in telling stories of environmental inequity and injustice through graphic design. Aneesa holds a BA in Human Ecology from College of the Atlantic and a Masters in Environmental Policy and Regulation at The London School of Economics.

This piece was commissioned as part of the Contextualising Climate Crisis series.

"[...] this is not climate leadership. It’s climate catch-up."

"[...] this is not climate leadership. It’s climate catch-up."

17th November 2021 / Article

A Green New Deal for Whom?

By: Dalia Gebrial

[...] this is not climate leadership. It’s climate catch-up.

"[...] this is not climate leadership. It’s climate catch-up."

The past few years have been something of a climate awakening in the Global North. Across Europe and North America, the movement to decarbonise our economy has not only become more organised, but the analysis of how we got here and who is responsible has become clearer. The imagination of what constitutes climate action has begun to be wrenched from the grips of liberal environmentalism – an ideology that abstracts our relationship with nature from how we run our political and economic systems. It is slowly dawning on us that we are staring down the barrel of 5 degrees warming by the end of this century, not because people don’t eat organic or have their own compost heaps. Rather, it’s because the way we have designed the modern world demands we exploit ourselves, each other and the world around us at all costs. From the Sunrise Movement, to Black Lives Matter, to the Youth Climate Strikers: the streets are making it clear that climate action cannot just be about reducing, reusing and recycling. It has to also be about revolting, resisting and rebuilding.

The Green New Deal Shift

At a policy level, this shift in thinking is being articulated through the framework of a ‘green new deal’. Although varying dramatically in their radicalism, most green new deals acknowledge that climate action cannot be about incentivising ‘greener’ individual behaviours. Rather, vast amounts of capital and political will must be channelled into reconstructing our society around renewable energy – creating public infrastructure and millions of ‘green jobs’ in the process.

To be clear, this is not climate leadership. It’s climate catch-up. Movements in the Global South and in Indigenous communities have been situating climate breakdown as an explicit product of colonial capitalism for decades. Their analysis has been actively and violently removed from decision making processes by the very institutions claiming to be at the forefront of climate action.

Yet, even as the penny starts to drop on the systemic nature of climate breakdown, we have not grappled with the global implications of climate breakdown, and our responses to it. Much of this stems from the legacy of Roosevelt’s original New Deal – which the Green New Deal builds on.

The New Deal’s Nationalism Problem

The New Deal was a historically exceptional example of the state intervening to shift resources away from capital and towards labour. It is true that it offered many working class North Americans a social safety net during a time of crisis. Yet, baked into this were the racialised and geographic exclusions that have always defined social democratic notions of ‘progress’. From redlining, to the internment of more than 100,000 Japanese people, there were strict boundaries around who was and was not included in Roosevelt’s vision of public investment. Indeed, the racialised inclusions and exclusions of the New Deal is summarised no better than in the image of Japanese internment camps being built by employees of the Work Projects Association, one of the largest state agencies set up under the New Deal.

What’s more, the New Deal was designed to be a distinctly national programme. It did not concern itself with the global impacts of the financial crash, despite the central role played by US institutions in creating the crisis. It also did not question the premise that the US can and should use its geopolitical power to secure its economic interests abroad – particularly in Latin America and the Caribbean.

It is within this context that we must scrutinise the assumptions underpinning Green New Deal frameworks emerging out of the Global North. Who is, and is not included in these visions of ‘green growth’ – and on whose backs is this development being built?

Good green jobs for whom?

One angle we can look at this from is that of ‘green jobs’. The green new deal promises Europeans and North Americans millions of secure, unionised jobs. Like the original New Deal, the vision is that these green jobs will be created through the building of massive public infrastructure projects, which will need to be built as part of a green transition – things like renewable public transport, green housing and solar panels. Rightly so, much of this has been focused on ensuring that already precarious oil and gas workers will not be abandoned in the shift to renewable energy. Rather, their expertise and skills are to be repurposed under a just transition. Research by Platform has found great appetite amongst offshore workers in the North Sea Oil for being part of such a change.

It is absolutely correct that the green new deal focuses on this workforce, who have a right to to be skeptical about the likelihood of a just transition. You only have to look at how successive governments have gutted and then abandoned industrial towns and cities, to understand why there’s little faith in the state to protect local communities during transition periods. However, when approached globally, this represents just one part of a much bigger story about work and climate crisis.

Without a global justice lens, visions of abundant public infrastructure fuelled by renewable energy in the North will be upheld by the exploitation of human labour and resources in the South. We must not forget what a renewable energy revolution looks like for those further down the supply chain, particularly those in industries that are assumed to continue – and possibly even expand – in a system based on renewable energy. Global production of batteries, solar panels, electric cars and wind turbines relies on rare earth minerals like cobalt that are overwhelmingly sourced from the Global South under horrific ecological and labour conditions. Not only does the digging of mines displace and endanger those living near them, but the mining industry is responsible for some of the most exploitative labour practices in the world. The International Labour Organisation found that in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where much of the world’s cobalt is extracted, 93% of the mining workforce experiences labour exploitation – many of whom are children as young as seven. As the demand for renewable technologies massively expands, downward pressure is worsening the working conditions of Chinese assembly lines.

Much of this demand is coming from companies headquartered in the Global North. The scale with which this expansion is taking place is driven by a ‘green growth’ agenda, which looks to essentially continue the current way in which our society is organised, but where carbon is replaced by rechargeable batteries and green energy. Existing visions of abundant green infrastructure in the Global North have not adequately grappled with what this means for the workers globally.

This is the danger of pursuing a green new deal that focuses primarily on workers in certain sectors or geographies of the supply chain – or that limits its imagination within national boundaries. The reality is that supply chains that make possible green technologies and other consumer or infrastructural products are transnational – and these supply chains are heavily implicated in any vision of a green new deal – global or otherwise. These workers, because of their geographic, class and racial locations, tend to be out of the purview of policymakers, especially in the global north. They are made vulnerable by some of the more West-centric green new deal discourses, despite being already at the sharp end of climate breakdown.

Care jobs are green jobs

Many of the working conditions that are most severely impacted by climate breakdown – and which will be heavily implicated in our responses to climate breakdown – are in forms of labour that aren’t even considered work.

Climate discourse in the Green New Deals of the Global North tend to focus on those masculinised industries deemed “productive” to GDP – like energy, transport and construction. However, the conditions of both paid and unpaid social reproductive labour – the work that goes into caring, cleaning, cooking and educating – tend to remain unaddressed. This is despite the fact that this kind of work is not only the building blocks upon which the rest of society relies, but it is essential to surviving climate-induced crises.

This is also part of the legacies left to us by the framework of Roosevelt’s New Deal, which transformed the working rights in many industries – but still relied on women doing the lion’s share of unpaid domestic labour in the home – and did not address the conditions of largely racialised, paid domestic work. This invisibilisation of domestic work is baked into capitalism itself. Today over 75% of unpaid care work in the world is undertaken by poor women and girls. Their contribution to the global economy when valued at minimum wage is $10.8 trillion – more than three times the value of the global tech industry.

Indeed, COVID-19 showed us what happens to the working conditions of women when crisis hits. When food supply chains are disrupted and care systems are overwhelmed, it’s marginalised women that absorb the fall out. They fill the care gaps, they strategise around food and energy stability and provide emotional and mental support to the community around them. Climate-related crises are no different. As our sense of stability is and will continue to be shaken, the labour of caring for one another will increase in its scale and intensity. A global green new deal must reckon with this, and ensure that women – particularly in the South – are not paying the highest price for climate breakdown. This means distributing social reproduction fairly, and building our infrastructures of mitigation and resilience around collectivising this labour and providing a material safety net for all.

Reimagining work

A key reason why the issue of global and gendered inequality continues to pervade our responses to climate breakdown is because we are still relying primarily on the political units of change that created this crisis. Units such as the nation-state, capitalist growth and patriarchal notions of ‘productive’ labour. There are of course practical reasons why some of our thinking needs to be articulated at the national level, but the existing model of nationally bound green new deals make it almost impossible to not reproduce colonial logics of green development – also known as ‘green colonialism’.

The green new deal can begin to work through these contradictions by re-imagining what it is actually trying to do. We often hear that the aim of climate action is to ‘save the world’ – understandably so given the loss of life we can expect if we continue as we are. But we must also be clear that we do not want to save the world as it currently exists; a world that engineers inequality in order to sustain its model of growth and development. We want to change the world. We want to change how we connect to one another, and what assumptions underpin the systems in which we live.

In the case of work – we want to change what it is we are working for: are we working to build more roads so companies like Amazon can provide next day delivery? Or are we working to make sure that we all have our care needs attended to in meaningful ways? Is the aim for everyone to have a 9 to 5 industrialised job in order to sustain unhealthy capitalist demand, or is it for the essential work of living to be distributed fairly, freeing up time for things other than work – things that give us joy, pleasure and safety? By asking fundamentally different questions, we create the space in which truly radical and global answers can begin to emerge.

The climate crisis presents us with an existential threat that requires a global response. But the scale of response needed also offers us a unique opportunity to do something much bigger than simply save work. It gives us the chance to reimagine it.

_

For more on what a global green new deal could look like, check out Dalia’s co-curated illustrated book ‘Perspectives on a Global Green New Deal’. You can order a copy of the book for free from www.global-gnd.com. You can also hear from activists from around the world in Dalia’s co-hosted podcast, Planet B: Everything Must Change, which explores the key pillars of a globally just green new deal. You can find Planet B wherever you get your podcasts. Supported by the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung with funds of the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development of the Federal Republic of Germany / the German Federal Foreign Office.

_

Dalia Gebrial is a PhD researcher at the London School of Economics. She is also an associate researcher at Autonomy UK, and co-author of Empire’s Endgame: Racism and the British State.

This piece was commissioned as part of the Contextualising Climate Crisis series.

3rd November 2021 / Video

Climate Justice From Below: Race, Class and Climate Crisis with Jhannel Tomlinson and Leon Sealey-Huggins

By: Jhannel Tomlinson & Leon Sealey-Huggins

3rd November 2021 / Video

Climate Justice From Below: Race, Class and Climate Crisis with Jhannel Tomlinson and Leon Sealey-Huggins

By: Jhannel Tomlinson & Leon Sealey-Huggins

Our #ReconstructionWork online conversation series continues with another special event with support from Arts Council England. In the global...

3rd November 2021 / Video

Climate Justice From Below: Race, Class and Climate Crisis with Jhannel Tomlinson and Leon Sealey-Huggins

By: Jhannel Tomlinson & Leon Sealey-Huggins

Our #ReconstructionWork online conversation series continues with another special event with support from Arts Council England.

In the global north and south, low-income communities are the first to experience the impacts of pandemics, water scarcity, power shortages, poor air quality and subpar living standards, which amplify vulnerabilities to extreme weather conditions. These communities are also agents of potent political resistance who have consistently advanced community-based solutions to the climate crisis that are often ignored, or silenced, by the mainstream.

On Tuesday 26th October, the Stuart Hall Foundation welcomed Jhannel Tomlinson, Cofounder of the Young People for Action Jamaica and GirlsCARE and is also the Sustainability Lead for the JAWiC board, and Leon Sealey-Huggins, Lecturer in Global Sustainable Development at the University of Warwick, to discuss intersectional approaches to addressing the climate crisis and its colonial roots. Coinciding with COP26, Jhannel and Leon will share their experiences, think through examples of community-based organising against climate antagonisms, and complicate corporate-led solutions to addressing climate change.

This event is a part of the Contextualising Climate Crisis Series. Read more here.

The Imagined Futures Series

"[...] resistance plants the seeds of a new society [...]"

"[...] resistance plants the seeds of a new society [...]"

28th June 2021 / Article

Reimagining Schools

By: Remi Joseph-Salisbury

[...] resistance plants the seeds of a new society [...]

"[...] resistance plants the seeds of a new society [...]"

In many ways, the pandemic has deeply unsettled the routines and rhythms of social life. That which seemed immovable or unquestionable suddenly appears much less perennial. The disruptions of the pandemic have been particularly apparent in education. In the UK, schools were closed or moved online and, almost unthinkably, examinations were cancelled or replaced by algorithms and then teacher predicted grades. As the UK begins to emerge from the pandemic, in education, as elsewhere, the conditions in which we find ourselves are ripe for exploring how things might be different; how things might be better.

Whilst some things may look less immutable, if we look beneath the surface, some things remain depressingly intransigent – this is evident in the global distribution of vaccines, as well as racial patterns in exposure to the virus and in responses to the pandemic (policing, for example). In education, specifically, the negative impacts of Covid-19 have been particularly detrimental for working class students, and students of colour. This was evident in the furore over how examination alternatives will (re)produce inequalities, and the way that the uneven distribution of resources (between schools and between families) have shaped capacities for home learning, exacerbating a ‘learning gap’ or, more accurately, a provision gap.

As we imagine brighter futures, propelled as we are by a sense that things will never be the same again, our task necessitates a focus on systemic transformation with the most marginalised in mind. This is not a question of simply rearranging the furniture but one of dismantling and rebuilding the whole structure.

Amidst the devastating impact of the pandemic, the grassroots education movement ‘No More Exclusions’ (NME) has insisted that we need a moratorium on school exclusions, an urgent call that has since garnered the support of the National Education Union, amongst others. They highlight the extensive use of exclusions through the pandemic, often in a deeply worrying attempt to ‘manage the additional pressures, turbulence and trauma of the pandemic and its impact on children and young people’.

NME’s call is important for at least three reasons. Firstly, it highlights, and pushes back against, the reliance on punitive and disciplinary responses to crises. Such punitive authoritarianism has been evident not only in schools but at the level of government which – consistent with the direction of travel in recent years – has put policing and ‘law and order’ at the heart of its response.

Secondly, and relatedly, the call is based upon a recognition that in schools, as in wider society, the effects of such approaches have been deeply racialised and classed. That is, a reliance on school exclusions, like a reliance on the police, disproportionately impacts upon working class and racially minoritised communities.

Thirdly, and crucially, NME’s call is important because it brings us to the question of imagined futures. It offers a glimpse of a brighter future, an indication of how we might transform society for the better. Though the call initially focuses on the pandemic period, particularly highlighting the need for care at a time of such monumental upheaval, it has the potential to serve as a catalyst for the permanent abolition of school exclusions: radical long-lasting change beyond the pandemic.

Amongst an abiding sense that things will never be the same again, the conditions seem ripe for social change. Imploring us to keep those at the sharp end in mind, NME’s moratorium shows how communities engaged in resistance can push to ensure that such change transforms, rather than reinforces, the status quo.

Imagining schooling without exclusions points to a more caring and nurturing education system. In this regard, the moratorium call ties in with the work of other campaigns to offer a fuller vision of a transformed education system. For instance, the work of the Halo Collective, a group of young Black organisers ‘fighting for the protection and celebration of Black hair and hairstyles’, points to a future in which school policies no longer discriminate against Black students and other students of colour, and the No Police in Schools campaign imagines a future in which schools are supportive environments free from the presence of police officers. Relatedly, the work of young activists at Body Count encourages us to imagine educational futures that looks to transformative, rather than punitive, approaches to justice.

As the Black Studies scholar George Lipsitz observes, ‘domination produces resistance, and resistance plants the seeds of a new society in the shell of the old’. With this in mind, those of us committed to social justice would do well to take these oppositional movements as a springboard for our imaginations.

Remi Joseph-Salisbury is a Presidential Fellow in Ethnicity and Inequalities at the University of Manchester. He writes on race, ethnicity, racism and anti-racism, particularly in the context of education and policing. He is co-author of the forthcoming ‘Anti-Racist Scholar-Activism’, author of ‘Black Mixed-Race Men’, and co-editor of ‘The Fire Now’. He has also authored and co-authored several reports recently on race and racism in education. He is a member of the Northern Police Monitoring Project, and the No Police in Schools campaign.

This piece was commissioned as part of the Imagined Futures Series.

"Addressing the social crisis and misery in front of us"

14th June 2021 / Article

Looking Back to Look Forward: Imagining a World Without State Violence

By: Liz Fekete

"Addressing the social crisis and misery in front of us"

14th June 2021 / Article

Looking Back to Look Forward: Imagining a World Without State Violence

By: Liz Fekete

Addressing the social crisis and misery in front of us

"Addressing the social crisis and misery in front of us"

14th June 2021 / Article

Looking Back to Look Forward: Imagining a World Without State Violence

By: Liz Fekete

The abolitionist call to ‘defund the police’ was dismissed tout court as ‘nonsense’ by Labour leader Keir Starmer last summer, after the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, and at the height of Black Lives Matter protests in the UK. Starmer added that he would have ‘no truck with that’, as his support for the police was ‘very, very strong’. More recently, home secretary Priti Patel declared herself in full agreement with a colleague who justified the police’s violent response to the Sarah Everard vigil on the grounds that it had been hijacked by ‘those who seek to defund the police and destabilise our society’.

At the heart of this knee-jerk rejection of the calls to ‘defund and divest’ is a distorted vision of abolitionism as a crude attack on the police that undermines a vital public service for the maintenance of the ‘natural’ order. However, if policing does not deliver safety and destabilises community life instead, shouldn’t we be able to advocate for alternatives? Increased funding for policing (new weaponry, the expansion of the immigration and counter-extremism units, the embedding of quasi paramilitary squads in multicultural working-class neighbourhoods) has coincided with neoliberal economic policies that privatise state assets and shrink the welfare state. Abolitionists’ daring response to the social crises that this has engendered is to suggest that we divest from ‘law and order’ and redirect resources upstream so as to address mental ill-health, fund youth clubs, build affordable homes, and counter the harms done by racism and sexism at their roots. That’s not ‘nonsense’, or ‘anti-police’, it’s a simple demand for a more rational and more humane use of resources.

Today, abolitionists are under attack from those who believe that the violence of policing is necessary to maintain the existing order. Imagining a world where state violence is no longer an acceptable way of resolving social problems necessitates an active engagement with history.

The tumultuous period we are living through is redolent of earlier periods when ordinary people rejected the existing order, whether it was the divine right of kings or tyrannical forms of governance. Rejecting the idea that history was made by the great and the good, or educated, professional modernisers, they set out to make history themselves, and abolitionist demands – far from being new – were at the centre of such calls for justice.

Today’s abolitionist arguments, associated with Critical Resistance and the Movement for Black Lives (MBL) in the US reverberate across continents and time, echoing the English Diggers of the seventeenth century (abolition of the aristocracy and property in land), Olaudah Equiano, Frederick Douglass, Ellen Craft, Robert Wedderburn and Harriet Tubman (abolition of slavery), the Communist organisers Rosa Luxemburg and Claudia Jones (opposition to militarism/abolition of imperialist wars), the Brazilian indigenous environmentalist and trades unionist Chico Mendes (abolition of the savage extraction of resources from the Amazon). And there are pre-democracy resonances too. For even before the existence of the modern state, subjugated people, rebelling against exploitation, illegitimate authority, cruel punishment and oppressive laws, spoke from their unique abolitionist frameworks. such as the 1381 Peasants Revolt against the poll tax. Taking advantage of periods when ‘the old world… is running up like parchment in the fire’, the leaders of rebellions, their visions of a fairer world immortalised in abolitionist tracts, voiced scepticism about institutions, beliefs and systems of punishment. Each and every one of these abolitionist thinkers were ridiculed and condemned in their times. Their persecutors were those who believed that the seemingly ‘natural’ order was sacred and immutable.

Looking back gives us the historical tradition in which to contextualise abolitionist demands but they do not explain the current moment. We need to acknowledge that the modern state and modern policing are very different to those of the past. It is the state that provides the authority and scaffolding from which all other violence flows – its power, to paraphrase Bertold Brecht, is the ‘storm’ that ‘bends the backs of the roadworkers’ – we need to understand how the state operates in the neoliberal context.

In a neoliberal market state – where government serves the interests of the market – state power is far less constrained than it was in the twentieth century. After the Chartists, and following the rise of the trade union movement, the industrial working class had bargaining power and clout. Today, the power of trades unions has been dissipated and working-class communities have been decimated by decades of neglect and austerity. Much of ‘law and order’, including the running of prisons, is provided by private security companies. Today’s private/public police corps keeps a lid on the crisis, while serving the interests of both state and market.

As shown by death after death in police custody (Sean Rigg, Leon Briggs, Kevin Clarke, George Nkencho, to name a few), the escalation of police force is lethal. If the police cannot be trusted to take someone experiencing a mental health crisis to a place of safety then we need to create a community corps trained in de-escalation techniques and motivated by a creed of care. This is what is meant by an abolitionist step based on a pragmatic demand to de-escalate violence.

This is the time when a dynamic counter culture to an unbridled capitalism can take root. But counter cultures can fail when they (however inadvertently) replicate the violence of existing power relations. Many of the social movements that we were involved with in the 1980s and 1990s failed to remove harmful power relations from their structures, replicating the state’s racism and patriarchy, for instance. State power today has become more opaque – and herein lies a new challenge for contemporary abolitionism.

Repeated panics about law and order, as Stuart Hall famously said, serve an ideological function related to social control, creating public support for ‘policing the crisis’. Under neoliberalism this involves mass criminalisation and an expanded prison state. It is not ‘nonsense’ to suggest we take money away from the police and redirect it upstream. What abolitionism offers is a road map to the future, which begins with addressing the social crisis and misery in front of us. If this is utopia, it is within reach.

“Progress is the realisation of Utopias” – Oscar Wilde, The Soul of Man Under Socialism (1891)

Liz Fekete is Director of the Institute of Race Relations and author of A suitable enemy: racism, migration and Islamophobia in Europe (Pluto press, 2009) and Europe’s Fault Lines: racism and the rise of the Right (Verso, 2018) which won the Bread & Roses award for radical publishing 2019. Active in anti-racist movements since the 1980s , she was an expert witness at the Basso Permanent People’s Tribunal on asylum and the World Tribunal on Iraq.

This piece was commissioned as part of the Imagined Futures Series.

"...studying how to feed ourselves..."

"...studying how to feed ourselves..."

1st June 2021 / Article

DINNER TIME

By: Imani Robinson

...studying how to feed ourselves...

"...studying how to feed ourselves..."

“The guerrilla studies! The guerrilla studies!” — exclaims Huey P Newton to an amorphous assembly of believers. The camera is zoomed a little too close to his face, abstracting him, abstracting expression. Huey is grieving, as one does when one is black and alive and a revolutionary. Grief is a revolutionary fervour, except when it isn’t.

I’m watching a documentary, piecing things together, studying I guess, that’s how you learn about the map, you listen to stories told by decipherers, you decipher, you study, you play.

A believer himself — you have to see it to believe it — Huey is stark, animated, severe, his body willing other bodies, to believe-see-become, to know for themselves the flailing common sense of deprival, to gather each other together, to gather in order to grieve-rename-articulate. To gather in order to trust.

Huey is grieving and/or I am grieving the dreams I did not or could not or would not author, but clung to nonetheless. Perhaps they are never dreams, instead, illusions. We are asleep for and/or to our dreams, awaking to persistent allusions of longevity and/or protection, illusions of a safety somehow unmade, uninsured insurance, ensured endurance.

Sleep! Where dreams come to live and die and be born, in the juice-dark renewal of rest. This is what happens in the dark, between dust and books and soil, left vulnerable to misinterpretation — is this, too, a tactic? — to the labour play of prayerful solutions, aghast, empty, disbelieving believers, containers of the lost colony, found over and again in jest, unjust, extrapolated and fed to children, to pigs rolled around and worn, as masks are and are not.

“The guerrilla studies!” — it’s been a riff slow roasting in the oven of my mind. I have painted it black and called it something holy, wrapped it up and swallowed it, hole. I have looked in the mirror and seen no answers, then I looked in other mirrors and saw some thing, discovered someone else that already discovered this; that other someone long ago and soon, who left some thing for the undead guerrillas.

In the annals of our freedom finding, we find our way, our treason trail. Feverishly, mouthful by unwholesome mouthful, we gather recipes, a cataclysm and another, again, we are reminded of the violence of this process, again, this blood-filled wreckage, its choppiness. We acquaint ourselves with the ingredients of our undoing, yes, we must be undone by our finding, our study — study will undo you — the this/them/that will graduate and be gone from our makeshift nests.

Won’t it? Will it? I? We? Us? All? Our pieces? What? Will be? Will be? — “The guerrilla studies!” — the warfare, the welfare, of the people — yours — people, which is to say community, except that it isn’t that simple, you can’t go around saying things like that, you won’t be believed, you won’t be able to believe it, and there must be something drifting beyond the sanctity of black and alive and revolutionary, something else in motion, tangible, in front of you. An imagined community, un-starved of touch, contactless, held because of it, within it, despite it — in order to spite it, this notion of a nation. We feel for each other in the night light.

To be sure, we must untether from this ghostly wifi, the unseverable connection of illusory cords, turns out your mother is a liar, if she ever was a mother, with all that interference. Abolition is — well, you will have to study it to be sure, — entailing admonition, admittance — in the future we will call abolition history, we will call it presence.

The guerrilla knows that the history of abolition is all around them, adding salt to taste, dividing portions, plating up, washing cutlery with an alkaline preparation. We grieving abolitionist guerrillas, having fessed up to our guilt, our deviant flagellant shame, having consented to each others flesh and mortified it, having been wrong wrong and wrong-er, without the rest of our maps — at a certain point your study will become you — we will eradicate this oppressive vocabulary of pretence, this warlike ledger, water-logged, waterlooed, blue as in hue, as in 14 and 92, hear we, re-membering our recipes, studying how to feed ourselves…

Imani Robinson is an artist and interdisciplinary writer whose practice combines performance, oration, poetry and critical theory, exploring themes of black geographies, the afterlives of transatlantic slavery, abolition and radical resistance. They are one half of Languid Hands, an artistic and curatorial collaboration with Rabz Lansiquot.

This piece was commissioned as part of the Imagined Futures Series.

"...a return to the non-imperial geography..."

"...a return to the non-imperial geography..."

17th May 2021 / Article

Rewinding Imperial History: A Pre-Bordered World

By: Ariella Aïsha Azoulay

...a return to the non-imperial geography...

"...a return to the non-imperial geography..."

An open letter to Achille Mbembe

Dear Achille,

I was recently invited to write about the “future” and was reminded of the workshop you organised twelve years ago in Johannesburg around the same theme. The most striking memory of the “future” I retain from my visit is not an argument or a paper, but rather the strong sensation of being in the future of a collapsed apartheid system, playing in my mind a fast-forward movement toward the future following the still-expected fall of the Israeli regime of occupation. I didn’t anticipate then that shortly after that visit, instead of fast forwarding, I’d experiment with an expansive form of rewinding that would actually bring me back to Africa. This time, I would go to its northern tip, and not as a guest, but as a native, a prodigal child.

You could not help thinking, you wrote to me after you read my open letter to Sylvia Wynter about the disappearance of Jews from Africa, that it was addressed to you too. You were not wrong. I have taken a break from writing the kinds of texts that are addressed to everyone and to no one in particular at the same time, and now I’m writing only letters, addressed to people whose language rebels against the spatial and temporal condition of empire. Reading your essays on Africa, I felt addressed by their speculative descriptions of a borderless world, and your notion of “redistributions of the earth.” Instead of fast forwarding toward a utopian project for the future, I’m interested in rewinding imperial history and thinking within the incompleteness of the past. Lately, I have been writing letters to my ancestors buried in North Africa, in the hope of awakening them from the slumbered colonial consciousness in which they were trapped, while they saw their descendants being hijacked by and into dissociated and manufactured histories and memories of other nation states. Disrupting imperial onto-epistemologies cannot be achieved without recalling our ancestors and stirring up their refusal of empire’s new realities and geographies.

I was born to an Algerian Jewish father but was not allowed to recognise myself as an Algerian Jew. With me, and others in my generation, thousands of years of Jewish life in North Africa were disrupted. I was born to a Palestinian Jewish mother. I was not allowed to recognise myself as a Palestinian Jew. I reclaim these two identities that were made unimaginable. To be what my parents were, became with the creation of the state of Israel and France’s obstinate refusal to decolonize Algeria following WWII, an onto-epistemological aberration that I nonetheless insist on embodying. I was born in 1962, in the year when the idiom “no longer” could be used to describe Arab Jewish life in the Maghreb, as if it were a bygone past. This “no longer” is imperialism’s signature, which aims to make Africa forget its prodigal children, but Africa listens to the sighs of their ancestors, who are ready to be awakened and recalled, and to attest to their own chagrin, after being left alone with no one allowed to come to hear what they still have to say.

In 1962, when I was born, Algeria, my ancestors’ home for thousands of years, was liberated from 132 years of colonialism. For many years, as I taught The Battle of Algiers, it was like teaching others’ anti-colonial struggles. Enraged, I was slowly awakening out of my own imperial slumber, and I came to understand that this film is about our people, Algerians, a people France told us we were “no longer” part of, as Israel then reaffirmed. During the battle of Algiers, the idea that Arab Jews would soon live there no longer was inconceivable. That it took decades of unlearning imperialism, and almost a decade of writing Potential History, for me to say I am an Algerian Jew shows how deep imperial human engineering goes and how entangled it is with what you call “risk management techniques.”

In the year when I was born, four basic facts disappeared from the global imaginary of the anti-imperial and anti-colonial annals: that the Jews in Algeria were colonised in 1830 like everyone else in Algeria; that they were endemic to Algeria no less than Muslims or Kabyle people among whom they lived; that in 1870 they were not granted citizenship but forced to become French citizens in their own country; and that decolonisation should have been their fate too, even if they had become French in some sense when they were made citizens of France. These facts, stirred from oblivion, become impediments to imperial progress.

I was born fourteen years after the Zionists destroyed Palestine and established Israel in its place. I was assigned the role of a weapon instead of an identity. Being “Israeli” means keeping Palestinians outside of Israel, making their return impossible and normalising the theft of their lands and property. At the same time, this command to live as a human weapon forces different Jews to gravitate toward a new violent common—Israel. This new common blurs their memories of having been diverse hyphenated Jews, whose history had little, if anything, to do with what was offered to them as their history—the history of the Jewish people, a historical subject crafted by Europe, whose destiny was to be fulfilled in Israel. I was made to forget my ancestors’ life and history in the Maghreb, and to prove, simply because I had been born on this land, that a state for the Jews in Palestine has a right to exist, regardless of the harm and the lies it produces to justify its existence. Its existence comes at the expense of people whose rights to live with others, in justice, while caring for their shared world, continue to be superseded.

The creation of the state of Israel was part of the “new world order” imposed by Euro-American imperial powers, who appointed themselves as liberators, while they continued to pursue genocidal practices in their colonies and in the settler-colonial spaces they crafted. A state for the Jews that European powers granted to the Jews, on lands they had no right to distribute, was a violent solution to the “Jewish problem.” This was what the Zionists, self-appointed representatives of the Jewish people, aimed to achieve, not the survivors of the Nazi extermination plans. The survivors’ urgent need to heal, wherever they found themselves at the end of the war as they recovered from campaigns of extermination and world destruction, were forfeited. Instead of redress, repair, and cessation of the imperial violence that these Euro-American powers had directed against different racialised peoples for centuries, Jews were offered a bargain: a state of their own that would make them just like others, a Judeo-Christian state apparatus programmed against Muslims and Arabs. The creation of the state of Israel was not for the Jewish people, but rather against many different Jews, primarily Arab Jews, whose life in North Africa and the Middle East was jeopardised by its creation and unsurprisingly was “no longer” within a few decades. Unlearning assigned identities is necessary for the past to become incomplete and for borders to collapse, so that a borderless world will not seem like an unattainable utopia but rather, like a return to the non-imperial geography that was stolen from our ancestors.

Yours, Ariella Aïsha, January 17th, 2021

Ariella Azoulay is an author, art curator, filmmaker, and theorist of photography and visual culture. She is Professor of Modern Culture and Media in the Department of Comparative Literature at Brown University. Her latest book is Potential History—Unlearning Imperialism (Verso, 2019).

This piece was commissioned as part of the Imagined Futures Series.

"In response to these failures there is a deep reimagining underway"

"In response to these failures there is a deep reimagining underway"

3rd May 2021 / Article

Revisiting Macpherson to Reimagine Public Safety

By: Alex S. Vitale

In response to these failures there is a deep reimagining underway

"In response to these failures there is a deep reimagining underway"

The Black Lives Matter movement has called for a global reckoning with the long history of anti-black racism and has specifically focused on the role of police in enforcing and enacting racial disadvantage. Included in their call to “defund the police” is a specific rejection of efforts to “reform the police” through interventions like training and community policing and instead focus on reimagining public safety independently of policing. This represents a sharp break with past efforts to eliminate racist policing.

In 1999 the Stephen Lawrence Inquiry found a problem of institutional racism within British policing. Officers had failed to take Lawrence’s murder seriously, had mishandled their relationship with the family, and showed a general indifference to the wellbeing of communities of colour. Later revelations exposed the fact that police were even surveilling the Lawrence family in order to undermine their efforts to hold police accountable. The ensuing Macpherson Report contained 70 recommendations designed to address racism within policing and the larger society. It included calls for police diversification, enhanced training around racial tolerance, and improved procedures for investigating racially motivated crimes all of which were designed to “increase trust and confidence in policing amongst minority ethnic communities.”

Twenty years later, significant gains have been made in hiring more diverse officers and implementing a variety of diversity and sensitivity trainings. And while more could be done, in theory, along these lines, there is little evidence that this has significantly reduced the disproportionate negative impacts of policing on communities of colour. Arrest rates, police use of force, and deaths in custody have not been reduced. Non-white communities continue to be over-policed. This should not be surprising, in part because the Macpherson report specifically said that there should be no change to underlying policing practices. They should just be done by a more diverse force with more racial sensitivity.

At the root of this problematic dynamic is the unwillingness of the Macpherson report or subsequent efforts to reduce racism through police reform to look at what is really driving deep racial inequalities. For the last 40 years the political leadership of the UK has largely capitulated to a politics of neoliberalism and austerity. In the face of global competition, they have cut services to those in need while subsidising the already successful through tax breaks and deregulation in hopes that they will become so successful that some of their new wealth will trickle down to everyone else. But this system has not produced widespread prosperity. It has produced a small group of extremely rich beneficiaries and growing precarity for everyone else. And the burden of this has fallen disproportionately on communities of colour. At the same time, it has fed racial resentment among white populations who have come to blame foreigners and racial minorities for their declining economic status.

The result of this has also been an increase in certain types of conventional street crime as well as problems of low-level disorder and the growth of so-called “vulnerable populations.” The management of these “problems” has fallen to the police. This has looked like increased police involvement in managing those who are homeless, young people acting out in schools, responding to mental health crisis calls, and intensively policing youth of colour across the board on the pretext of stopping drugs or violence.

In response to these failures there is a deep reimagining underway of what public safety could look like independent of the criminal legal system. A growing number of people are calling for replacing police-centred strategies with community investments and commitments to long term strategies for producing greater racial and economic justice. Groups like the 4Front Project in London are demanding that government address the very real problem of youth violence by investing in youth instead of police. They take a youth centred perspective that understands the challenges young people face in a hostile environment in which their families are in crisis, schools lack resources, and the prospects of long-term stable employment seem non-existent. Any effort to produce real safety for young people must start with stable housing, family supports, access to high quality schools, and the prospect of upward mobility.

Similarly, Kids of Colour in Manchester is demanding that schools become sights of safe and successful learning, rather than extensions of the criminal legal system or as we say in the US, “the school to prison pipeline.” As young people face increasing pressures at home and in the community just as educational and social supports are diminished, this is producing disruptive behaviour in and around schools. Rather than framing this as a discipline problem to be counteracted by increased suspensions and policing, they are demanding more resources for schools and the families of these young people.

This kind of reimagining of public safety asks us to reject the false equating of justice with punishment and to instead invest in new systems of justice rooted in restoring communities and individuals so that fewer harms are experienced including those inflicted by the criminal legal system. These “restorative justice” approaches work with young people to develop real interpersonal and communal accountability and to take steps to repair past harms and prevent new harms from occurring.

Racial justice is not going to come from a black police officer, it’s going to be achieved by addressing racism in a broad array of institutional settings such as housing and employment discrimination, unequal funding of social services and infrastructure and the failure to come to terms with the legacies of slavery and colonialism at the root of these ongoing disparities.

Alex S. Vitale is Professor of Sociology and Coordinator of the Policing and Social Justice Project at Brooklyn College and a Visiting Professor at London Southbank University. He has spent the last 30 years writing about policing and consults both police departments and human rights organisations internationally. Prof. Vitale is the author of City of Disorder: How the Quality of Life Campaign Transformed New York Politics and The End of Policing. His academic writings on policing have appeared in Policing and Society, Police Practice and Research, Mobilisation, and Contemporary Sociology. He is also a frequent essayist, whose writings have been published in The NY Times, Washington Post, The Guardian, The Nation, Vice News, Fortune, and USA Today. He has also appeared on CNN, MSNBC, CNBC, NPR, PBS, Democracy Now, and The Daily Show with Trevor Noah.

This piece was commissioned as part of the Imagined Futures Series.

"Where colonialism universalises the future, we must not."

19th April 2021 / Article

Imagining the Unimaginable as Everyday Practice

By: Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan

"Where colonialism universalises the future, we must not."

19th April 2021 / Article

Imagining the Unimaginable as Everyday Practice

By: Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan

Where colonialism universalises the future, we must not.

"Where colonialism universalises the future, we must not."

19th April 2021 / Article

Imagining the Unimaginable as Everyday Practice

By: Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan

Where colonialism universalises the future, we must not. Where it disciplines all possibility to serving the needs of capital, our imaginings must refuse to. Where it presupposes European Whiteness as the final destination, we must swerve elsewhere, or be killed, and our imaginings of what next must leave no such room for exception. To outmanoeuvre the grasps of coloniality we must project forward in un-intelligible ways!

I say this because when imagining the future, it is tempting to seek blueprints. What, specifically, will those accountability processes look like when policing is abolished? How, exactly, will we organise society after nation-states and borders are dismantled? To seek concrete answers tends to universalise Eurocentric ‘solutions’ once again, and our inclination for ‘alternatives’ forgoes the possibility of leaving some things entirely behind. Instead of standardised ‘replacements’ perhaps the future should look a million different ways, filled with multitudes and uncertainty.

It is not an-other world that requires imagining. It is many, authored by many. And it is in the process of crafting the tools to build parts of what we can imagine, that what we could never imagine might manifest. ‘Let’s make new tools to dismantle the house’, could become an unexpected journey to kindling a fire that eats it up instead. Or, crafting what turns out to be a digging implement that collapses the house onto itself. Or, tearing open a dam elsewhere that drowns the house in ways never considered before.

It is tempting to look for Big Moments in the past to draw inspiration for this. Revolutions, insurrections and rebellions. But I am more interested in the overlooked imaginative practices of those whose world is an-Other world already. The practices of racialised, disabled and immigrant women, whose unglamorous practices make different futures possible all the time.

I am thinking about the immigrant women who told me they pretended not to understand instructions of factory bosses. Their playing on racist assumptions claimed an alternative timeline altogether. One which refused commodification into surplus value for the company, resisting racial capitalism’s claims to the entirety of their future. I am thinking of the kameti and pardner systems that migrant communities have used to pool, borrow and lend money without having their futures imprisoned to debt bondage through interest charges of banks who bend all futures to their subservience. Mutual care networks of disabled people disorder space/time by disobeying the demand to direct all futures towards the most valuable output for capital. By directing their worlds towards the wellbeing of lives deemed ‘unproductive’ excess, they invest in the inconceivable. The everyday de-escalation of conflict often shouldered by women – ‘that toy belongs to both of you! you have to share!’ – is a vision of collective ownership that disrupts the idea that property ownership must necessitate exploitation and dispossession.

So many different nows already exist that are unthinkable to the colonial imaginary. They create worlds we are told are impossible or would require years of reform but cannot be instated overnight. But our worlds are changed overnight by detentions, raids, arrests and assaults all the time. Impossibility is simply the vocabulary of those invested in the status quo. Their vocabulary aims to naturalise a deeply constructed world where genocidal policies are called ‘immigration controls’; imprisonment is ‘protecting us’; exploitation is ‘the 9 til 5’. When we give other names to this world, we make visible the fact many things we are told are natural, are man-made. This is not mere rhetorical squabbling. Anything man-made holds the possibility of being unmade, so the names we give not only reveal other nows, they make claim to other futures altogether.

Therefore, small, everyday practices can prick holes in the universalising future coloniality has draped before our eyes. Those practices are often rooted in the most derided of revolutionary forces: love and care. Because that is exactly where the most unimaginable futures stem from. From racialised and disabled people daring to imagine we might make it into the future. Undocumented people daring to imagine safety and reunion. To imagine ourselves not only alive, but laughing in our own futures, necessitates the end of the world as we know it and asserts space for a multiplicity of futures that might get us there. Afterall, our futures must not only be utilitarian.

When we imagine redistributed global resources; harm resolved by addressing material conditions instead of criminalisation; an end to imperialism in its military, ecological and development forms; or anything else – those imaginings are not ends in themselves. They are the bare minimum we can imagine, as a means to a future in which we may exist in ways beyond what we can imagine. Not just where we might have beyond our imagination, but where we might live, think, learn, heal and worship in ways beyond our wildest dreams.

Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan is an educator, award-winning poet and published writer from Leeds. She is the author of poetry collection, Postcolonial Banter, co-author of the anthology, A Fly Girl’s Guide to University: Being a woman of colour at Cambridge and other institutions of power and elitism; co-essayist in I Refuse to Condemn: resisting racism in times of national security, and host of the Breaking Binaries podcast. Her work disrupts common understandings of history, race, knowledge and power – particularly interrogating the purpose of narratives about Muslims, gender and violence. She is published in The Guardian, Independent, Al-Jazeera, gal-dem and her poetry performances have millions of views online. Suhaiymah is currently a Visiting Research Fellow at Queen Mary University of London and her poetry, articles and books can be found on University and school syllabi.

This piece was commissioned as part of the Imagined Futures Series.

Essays

"the Coronavirus Pandemic from a perspective which is both socio-political..."

"the Coronavirus Pandemic from a perspective which is both socio-political..."

11th October 2020 / Article

The Coronavirus Pandemic and its Meanings

By: Michael Rustin

the Coronavirus Pandemic from a perspective which is both socio-political and psychoanalytic

"the Coronavirus Pandemic from a perspective which is both socio-political..."

The Article has been published in the Revista Brasileira de Psicanálise volume 54 numero 2 , 2020

Abstract

This article examines the meanings of the Coronavirus Pandemic from a perspective which is both socio-political and psychoanalytic. It suggests that the concept of “combined and uneven development” is relevant to understanding the events which are now taking place. This is because the pandemic has brought together the genesis of a new disease in conditions where the interface between society and the natural world is unregulated, but also where modern forms of communication have enabled an unprecedentedly rapid spread of the disease to take place, across the entire globe. Multiple lines of social division are being exposed by the crisis, as social classes, ethnic populations, nations and regions are differentially harmed. Contrasting priorities, ideological in origin, are being revealed in governments’ response to the virus, in the commitment they give to the preservation of lives compared with other material interests.

In a second part of the article, psycho-social dimensions of the crisis are explored. A psychoanalytical perspective focuses on anxieties as these are generated by the extreme disruption and risks posed by the crisis. It is suggested that these are not only conscious but also unconscious, giving rise to destructive kinds of psychological splitting and denial, and disrupting capacities for reflective decision-making. It is argued that a loss of “containing” mental and social structures is now having damaging effects, and that their repair may be the precondition for constructive resolutions of a general social crisis.

___The Revista is a journal devoted to psychoanalysis, but the explanation of the causes and consequences of the pandemic (from which at the time of writing Brazil seems to be suffering most in all the world) has many aspects which are not best captured by psychoanalytic explanations. Before reflecting on how a psychoanalytic paradigm can engage with this ongoing tragedy, I would like to sketch out an understanding of the pandemic’s wider social and political dimensions. Surprisingly, a theoretical model which does illuminate the current situation is one set out by Leon Trotsky in his explanation of the distinctive attributes of the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, in his history of the Russian revolution (1932). This was his “Theory of Combined and Uneven Development.” His argument was that what had made the revolution possible was the presence in what was essentially a backward Russian society of some exceptionally “modern” and developed sectors. Among these were a flourishing industrial capitalism, an organised working class, and an advanced intelligentsia, of whom the Bolsheviks and other communists, socialists and anarchists comprised one element. But what condemned the revolution to extreme difficulties, and ultimately, given the choices that were made, to its deformation and failure, was the fact that this “modern” segment existed within a system which mainly consisted of semi-feudal means of agricultural production (serfdom had only been abolished in 1861) an illiterate peasantry, religiosity and superstition, and an autocratic and brutal form of government by the Tsarist state. This was, even in when it was published in 1932, a prescient analysis of the situation which the revolutionaries had faced, and which led to the eventual defeat of their modernising project. Justin Rosenberg, Professor of International Relations at the University of Sussex, has recently revisited this theoretical model (under the reversed name of Uneven and Combined Development) to explain contemporary geo-political developments.(Rosenberg 2013).

How can this theoretical model of change be useful in explaining a crisis as different from a social revolution as the current global pandemic? The explanation lies in the conjunctions of the effects of some highly advanced and some “early” and backward aspects of social and economic development, which are each relevant to these very different phenomena, a revolution and a pandemic. It seems likely that the virus had its biological origins in food markets in China in which trade in live animals captured from the wild and slaughtered without preventive hygiene at the point of sale, was combined with many other forms of commerce in domestic animals and other foodstuffs. It was possible in those conditions (as with earlier epidemics such as SARS) for a virus to cross species, perhaps with intermediate wild animal vectors such as bats. This is the “pre-modern” element of the situation, one which has probably had many precedents in the mutation of diseases.

Superimposed on this close contact in food markets between the organs and diseases of wild animal species, and their human traders, (which we describe as a pre-modern form of commerce) has been the exceptional speed of transmission of this disease, which has been due to the rapid flow of human beings across the globe that takes place in the highly-modern modern communications environment. This has been described by one sociologist of globalisation as a “space of flows”, a concept developed within the elaboration of the theory of globalisation by many scholars (e.g. Beck 2000, Castells 1998, Giddens 1991, Harvey 1989, Massey 2002 and Urry 2007) in recent decades. Many component features of globalisation were predicted within this model, including the rise of global trade, vast and almost instantaneous flows of finance capital, and the central role of information technology among its generative features., And, as its negative by-products or “feedbacks”, the emergence of “fundamentalist” resistances to modernisation, large flows of refugees, and even global terrorism. It has turned out that another consequence of this situation of combined over- and under-development has been the exposure of the entire world’s population, in the space of just six months, to a virus, Covid 19, which health and social systems have so far mostly been unable to suppress. Prior to Covid 19 there were other viruses, such as HIV, Sars, and Ebola, which have been barely contained, and from which insufficient lessons were learned. Of course plagues have always afflicted humankind, such for example as the “Spanish flu” which killed millions after the First World War. What is singular about this one is the exceptional scope and speed of its transmission. One can say that it is fortunate that it is not even more lethal in its effects than it is.

There are other aspects of “uneven development” relevant to the pandemic, in addition to the one I have mentioned. Its impact is disclosing large differences in the vulnerability of populations to the virus, and in the capacities of social systems to contain it. These differences are in part a function of relative material wealth, as has always been the case with the incidence of epidemics. It is much more feasible for privileged social groups to isolate themselves, or flee to relative seclusion, than it is for the poor, in particular for those living in absolute poverty. (It was common in cities in Renaissance Europe for elites to take refuge in rural retreats in this way.) These differences are also a consequence of the quality and amount of resources invested in public health systems – the availability of doctors, hospital beds, testing and tracing facilities, reliable data etc. But levels of material wealth – average per capita income – are by no means the only significant cause of variance in the harms caused by the virus. It appears that differences in the ideologies and power-structures underlying social systems are also critical in shaping its effects.

It is striking, for example, that European nations have for the most part achieved far better outcomes than are being achieved in the United States in the management of Covid 19. Within Western Europe, the United Kingdom however (excepting Scotland, which has an autonomous public health system) has done conspicuously worse than its European equivalents, after a period when Spain and parts of Italy were overwhelmed by the first impact of the virus. China and other nations in South-East Asia have been substantially more capable in taking action to contain its effects than most other areas of the world. States in India which already had effective public health systems (some of them with histories of Communist regional and city government) have achieved better outcomes than some which did not. Readers of this journal will need no reminding of the disaster now befalling Brazil, where denial of the public health responsibilities of a government, indeed of the reality of the disease itself, is combining with long-standing inequalities of condition to facilitate the epidemic spread of the disease.