Stuart Hall in Translation: Brazilian Portuguese, with Bill Schwarz and Liv Sovik

- What can be lost and gained when texts are translated into different languages?

- Can ideas form linkages across difference?

- How can ideas transcend spatial and temporal boundaries?

- What are the political implications associated with ideas moving across and between boundaries?

To initiate the project, we invited Bill Schwarz, co-author of Stuart Hall’s memoir ‘Familiar Stranger’, and Liv Sovik, professor of Communication at Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, to discuss the nuances of translating ‘Familiar Stranger’ and Hall’s ideas into Portuguese for a Brazilian audience.

You can listen here to the conversation with Bill Schwarz and Liv Sovik, which was recorded in August 2022, and is introduced and hosted by SHF Director Orsod Malik.

In 2024, we extended the invitation to other translators of Hall’s work, asking them to write about their own experiences, and addressing the disparities, challenges, and synergies of translating Hall’s ideas into a different language and national context. These new texts will be published in Cultural Studies Journal and on the Stuart Hall Foundation website in Autumn 2024.

A transcript for this conversation will be published on this page soon.

Sign up to the SHF newsletter to keep updated!

Supported by Taylor & Francis.

The speakers

Bill Schwarz is Professor of English at Queen Mary University of London. Bill’s many publications include his Memories of Empire trilogy and his contribution to Stuart Hall’s memoir Familiar Stranger. A Life between Two Islands (2017). With Catherine Hall, Bill is also General Editor of the Duke University Press series, The Writings of Stuart Hall.

Liv Sovik is a full professor at the School of Communication of UFRJ. She is a collaborating professor of the Ethnic and Racial Relations Masters, CEFET-Rio de Janeiro, and researcher of the PACC Advanced Program in Contemporary Culture, UFRJ. She edited a major collection of Stuart Hall’s works into Portuguese, Da Diáspora: identidades e mediações culturais (Editora UFMG, 2003), and is the author of Tropicália Rex (Mauad, 2018) andAqui ninguém é branco [Here No One is White] (Aeroploano, 2009).

The Stuart Hall Foundation’s Reading the Crisis series asks: what kinds of tools and strategies are needed to address this conjuncture? This online conversation series seeks to advance Stuart Hall’s thinking by analysing a curated selection of three of Hall’s essays in relation to present-day political formations. Each conversation, chaired by Aasiya Lodhi, forms an online teach-in space dedicated to demonstrating how engaging in a conjunctural analysis can enrich artistic practice, deepen organising work, and academic study.

The second event in the series took place on Monday 24th June 2024, featuring Aditya Chakrabortty and Jeremy Gilbert responding to Stuart Hall’s 2011 essay ‘The Neoliberal Revolution’ in order to better understand today’s political milieu.

Read a transcript of the event here:

https://www.stuarthallfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/RTC-Episode-2-Transcript.pdf

Coming up in the Reading the Crisis series:

23rd July – Cultural Identity and Diaspora

Learn more: https://www.stuarthallfoundation.org/events/

In partnership with Duke University Press supported by Esmée Fairbairn Foundation and Barry Amiel and Norman Melburn Trust.

Reading the Crisis is part of the Stuart Hall Foundation’s Catastrophe and Emergence programme. Learn more about Catastrophe and Emergence here:

https://www.stuarthallfoundation.org/projects/catastrophe-and-emergence/

In October 2023, we were pleased to host an event to welcome new members joining the Scholars, Fellows and Artists Network. The event was an opportunity to develop connections between new scholars and with the Stuart Hall Foundation, allowing them to meet and share ideas in-person. Attendees were invited to introduce their research, explore Stuart Hall’s thoughts on what it means to be a public intellectual, and learn more about the Foundation’s programme of events, workshops and opportunities available to them.

Following a group discussion responding to clips from Hall’s lecture ‘Through the Prism of an Intellectual Life’, participants were invited to visit the Courtauld Gallery’s major exhibition of artist Claudette Johnson’s work, Presence. Claudette Johnson later joined participants in a collective conversation around her career and the nuanced processes and decision-making in her approach to visual art.

The Stuart Hall Foundation’s Reading the Crisis series asks: what kinds of tools and strategies are needed to address this conjuncture? This online conversation series seeks to advance Stuart Hall’s thinking by analysing a curated selection of three of Hall’s essays in relation to present-day political formations. Each conversation, chaired by Aasiya Lodhi, forms an online teach-in space dedicated to demonstrating how engaging in a conjunctural analysis can enrich artistic practice, deepen organising work, and academic study.

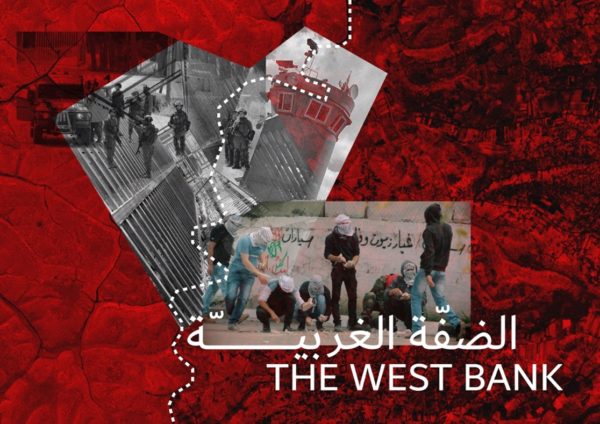

The first event in the series took place on Tuesday 7th May 2024, featuring Ilan Pappé and Priyamvada Gopal responding to Stuart Hall’s 1992 essay ‘The West and the Rest: Discourse and Power’ as a means of making sense of the conflicts of today.

Read a transcript of the event here:

https://www.stuarthallfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/RTC-Episode-1-Transcript.pdf

Coming up in the Reading the Crisis series:

24th June – The Neoliberal Revolution

23rd July – Cultural Identity and Diaspora

Learn more: https://www.stuarthallfoundation.org/events/

In partnership with Duke University Press supported by Esmée Fairbairn Foundation and Barry Amiel and Norman Melburn Trust.

Reading the Crisis is part of the Stuart Hall Foundation’s Catastrophe and Emergence programme. Learn more about Catastrophe and Emergence here:

https://www.stuarthallfoundation.org/projects/catastrophe-and-emergence/

To coincide with the Annual Stuart Hall Public Conversations that take place each year, we invite members from our Scholars, Fellows and Artists Network to participate in an in-person event. These network events are dedicated to fostering critical engagement and collaboration among scholars, artists and practitioners. They embody the purpose of our regular network gatherings: to facilitate interdisciplinary dialogue, nurture intellectual development and provide support for underrepresented practitioners.

On Friday 22nd March earlier this year, we hosted a workshop at Conway Hall in London. Led by Remi-Joseph Salisbury and Laura Connelly, authors of Anti-Racist Scholar-Activism (Manchester University Press, 2021), this dynamic forum explored anti-racist scholar activism amidst the confluence of crises scholars, artists and practitioners are navigating in their respective fields at this time.

We commissioned a member of our Scholars, Fellows and Artists Network, CJ Simon – currently a PhD scholar with the White Rose Doctoral Training Partnership – to share his reflections following the event, included below:

“In a time where it can feel quite lonely to be a Black academic, I am forever grateful for the work of the Stuart Hall Foundation. On 22nd and 23rd March, the foundation took over Conway Hall to host two exciting events; the first was an ‘Anti-Racist Scholar Activist’ workshop run by Dr Remi Joseph-Salisbury and Dr Laura Connelly, the second a Public Conversation between the acclaimed installation artist and filmmaker Isaac Julien and the incomparable writer and curator Gilane Tawadros. Whilst very different in form and substance, both events promised to bring together a wide network of scholars, artists, practitioners, and members of the public invested in producing a more equitable world. Boy, did it deliver. Over those two days there was an electric pulse of conversation between attendees stretching out from Conway Hall to the pubs and cafés dotted around London, all centred around our lived experiences, struggles, hopes, and plans for carving some kind of path forward. Lonely no longer.

“As a theatre-maker and PhD researcher interested in understanding how communities can come together to shape political opinions and behaviours, there was something incredibly refreshing about a workshop so devoted to praxis: talking through how our theoretical work can and should lead to real-world practice. This conversation was perfectly contrasted with the screening of Isaac Julien’s ‘Once Again… (Statues Never Die)’, a film which very poignantly asks the audience to reflect on the colonial relationship between history, art, and intimacy. Vindicating the writing of Stuart Hall, Julien’s piece demonstrated to me just how crucial art is to the practical work of anti-racist activists. A lovely feeling for someone who came into academia through the world of poetry and theatre.

“Surprisingly, the most exciting – and probably most radical – thing to come from this weekend hasn’t actually happened yet. In finding new friends, new peers, and new mentors to talk with, disagree with, and learn from, I know that the work has only just begun. The community is growing and expanding and finding a way to sustainably fight for an equitable world.”

The Anti-Racist Scholar Activism Workshop was supported by the CoDE ECR Network

For the 7th Annual Stuart Hall Public Conversation, the Stuart Hall Foundation welcomed acclaimed filmmaker and installation artist Isaac Julien. The event took place on Saturday 23rd March 2024 at Conway Hall, London, inaugurating our Catastrophe and Emergence programme.

Isaac’s keynote presentation explored the connection between image-making and political allegory. He drew upon his conversations with Stuart Hall over the years to reflect on how ideas, language and narratives can transform within a visual frame, presenting new modes of the imaginary. “Stuart’s double position,” Isaac reflected, “eagerly greeting this new wave of left-wing thought but subjecting it to rigorous critique, was instrumental in helping me form my own path through the stories that my research turned up.”

The event also included a new, two-screen presentation of Isaac Julien’s immersive installation, Once Again… (Statues Never Die). Tapping into his extensive research in the archives of the Barnes Foundation, Isaac’s film considers the reciprocal impact of Alain Locke’s political philosophy and cultural organising activities, and Albert C. Barnes’ pioneering art collecting and democratic, inclusive educational enterprise. This was the first time the piece was shown in this format in the UK. Following the screening, Isaac was joined in conversation with Gilane Tawadros, Chair of the Stuart Hall Foundation and Director of the Whitechapel Gallery. An audience Q&A also took place, and Newham Bookshop provided a stall for attendees to browse from.

Additionally, the inaugural Stuart Hall Essay Prize was awarded to its first winner, Hashem Abushama, for the essay “a map without guarantees: Stuart Hall and Palestinian geographies”. Trustee and judging panel member Catherine Hall presented the award to Hashem, whose acceptance speech provided additional valuable context to the essay’s creation and content.

In partnership with Conway Hall supported by Esmée Fairbairn Foundation, Barry Amiel and Norman Melburn Trust and Cockayne Grants for the Arts, a donor-advised fund held at The London Community Foundation.

The Stuart Hall Essay Prize

The Stuart Hall Essay Prize was launched in August 2023, inviting new and unpublished writing that connected with Stuart Hall’s ideas and impacted broad public discourse. The prize was intended for a selected writer whose essay engaged with and offered originality and value to a field of debate with which Hall engaged throughout his life, and contributed to a radical critique of contemporary society.

At the 7th Annual Stuart Hall Public Conversation in March 2024, the inaugural Stuart Hall Essay Prize was awarded to Hashem Abushama for the essay “a map without guarantees: Stuart Hall and Palestinian geographies”. The judging panel, composed of Catherine Hall, Jo Littler and Kennetta Hammond Perry, described the essay as “a powerful, politically important and theoretically nuanced piece of work written in lyrical prose… that elicits an urgent reckoning with ongoing realities of violence of dispossession, but with an eye toward imagining more just futures.”

Hashem Abushama’s prize-winning essay is published in full below. The author would like to thank Haya Zaatry for her indispensable help with this essay, particularly for her design of the countermaps.

a map without guarantees: Stuart Hall and Palestinian geographies

I could not locate the entrance of al ‘Arub refugee camp, where I grew up. The settlement was to my right. Driving on the main carriageway, shared between the Israeli settlers and Palestinians, I expected to get to the camp’s entrance without any turns. This was the map I had known. To my surprise, the carriageway took an elevation as if one was suddenly driving towards the sky. It then cut into the hill to the south of the camp. There was a new right turn marked by a red sign in Arabic and Hebrew, clearly declaring this territory as Palestinian and warning Israeli settlers against entering it. After a roundabout, I got to the camp’s entrance where an Israeli checkpoint was in place. My house is the first in the camp, so near the checkpoint that I eavesdrop to the soldiers’ conversations and music.

This is the 60-Route, a 146-mile running from al Nasira (Nazareth) in northern historic Palestine (today’s Israel) all the way to Beer Saba’ (what Israel calls Beersheba) to the south. The road stretches from the north to the south because of historic/continuous dispossession, restricting the Palestinians’ right to movement. Changing the fabric of life around al ‘Arub is part of a wider Israeli project that aims to better connect Tel Aviv and Jerusalem to Jerusalem’s surrounding settlements and to the settlements in southern West Bank. The project unfolds in a particular historical conjuncture defined by intensified privatization of the Israeli economy since 1985 (see Hanieh 2003; 2013), the introduction of the self-ruling Palestinian Authority in 1993 (see Rabie 2021), and the fragmentation of Palestinian geography and polity (Salamanca et al 2012).

Despite the increasing reliance on capital to exact the control, management, and elimination of the Palestinian population, colonial relations remain the most constitutive. While in this conjuncture the dispossession of the Palestinians may take forms that directly exploit or contradict the capitalist relations, the unfolding of such relations happens against the backdrop of what Glen Coulthard (2014, 15) calls the “inherited background field” of colonial relations. This already begs the question of how we understand the frictions and mediations between the different levels of a social formation: between a privatising market and a settler colonial road, a Zionist ideology and a settler colonial state, a consumerist subjectivity and an arts organization.

I came of age at a time when taking loans, purchasing private cars, and aspiring to move to ‘the city’ (i.e., Ramallah) were becoming a norm in the West Bank (see Harker 2020). This is capital making a larger claim on defining the horizon of possibilities for the colonized Palestinian subjects. This is capital unfolding alongside patterned axes of difference: what capital makes available to you is eclipsed by structured patterns informed by gender, race, class, and nationality. If capital is increasingly playing a primary role in Palestine and across the world, how do we make sense of its relations to settler colonialism and its mediation through those axes of difference? This is the question that brought me to Stuart Hall and his writings.

Settler colonialism is a complex set of relations, practices, and processes that get condensed into durable yet historically contingent institutions, eliminatory spaces, and ideologies. It seeks to implant a settler way of life in place of the indigenous. As Wolfe (2006, 387) argues, settler colonies are “premised on displacing indigenes from (or replacing them on) the land.” They do so through positive (e.g., recognition and assimilation) and negative (e.g., genocide and disenfranchisement) mechanisms. Writing on settler colonialism, Coulthard (2014) shows how, in its economic reductionism and developmentalism, orthodox Marxism fails to consider the constitutive and continuous role of dispossession, particularly in settler colonial contexts. This contradicts Marx’s idea of ‘primitive accumulation,’ which relegates violence to a bygone historical moment (see Levien 2015). Given the continuous use of brute violence by settler colonial states to dispossess the indigenous, including Israel’s latest genocide in Gaza and the United States’ attempt to dispossess indigenous communities in Standing Rock (see Estes 2019), there arises the political and conceptual necessity to understand dispossession as contemporarily constitutive.

Starting with space gives us a generative entry point into the ‘concrete historical work’ that settler colonialism achieves in each spatio-historical conjuncture: “as a set of economic, political, and ideological practices, of a distinctive kind, concretely articulated with other practices in a social formation” (Hall 2021, 236). Doreen Massey (2000, 225), citing a regular lift to work with Stuart Hall, proposes we understand space as produced by interrelations. Space is not fixed. “You are not just travelling across space; you are altering it a little, moving it on, producing it. The relations that constitute it are being reproduced in an always slightly altered form” (Massey 2000, 226).

The settler road is concrete, a material and spatial manifestation made possible through practices (stealing the land from the indigenous, building the road, and surveilling it with military watch towers), institutions (the military and supreme courts, municipality, and corporates), and processes (e.g., capitalism and colonialism). The settler state and the corporates get to decide how and where the road passes through. But that does not mean they are the only ones producing that space; such a view, Massey (1994, 40) suggests, ‘deadens space.’ I, a subject of military occupation and an afterlife of refugees displaced in 1948, produce the road as a space by passing on and living alongside it.

If space is made up of multiple intersecting relations, then there is a multiplicity in this production which unfolds within an open system and on an unequal terrain. The result is neither total incorporation of the native Palestinians into settler colonial spaces, nor a total reclaiming of space. It is a “continuous and necessarily uneven and unequal struggle” (Hall 2021, 354). This is a map without guarantees[1], one that sees processes and things as constituted by relations; relations as historically contingent and particular; and relations as prone to rupture and transformation. This is a map without guarantees, where settler colonialism may, one day, cease to exist.

In this essay, I write a theoretical diary, informed by Stuart Hall’s writings, that traverses the refugee camp, the village, and the city. It is part of a wider project that animates Stuart Hall’s thought by examining its remits and limits when thinking about settler colonialism across historic Palestine. In particular, I use Stuart Hall’s insistence on ‘conjunctural analysis’ to demonstrate how 1) there exists multiple Palestinian geographies; 2) how such geographies stand in relations of domination and subordination vis-à-vis one another and the Israeli state; and 3) how such geographies remain prone to rupture and transformation. I use countermaps designed for the essay by Palestinian architect and musician Haya Zaatry as well as photographs I have taken of the different geographies. I use ’48 territories to refer to Palestinian territories that had been occupied in 1948, ’67 territories to refer to the lands occupied in 1967, and ‘historic Palestine’ to refer to the entire land, engulfing both the ’48 and ’67 territories. This is not only consistent with how Palestinian communities, scholars, and activists name these territories, but also integral to any attempt to understand the continuous yet differentiated logics of dispossession across historic Palestine.

1. The camp

“In recounting the story of someone born out of place, displaced from the dominant currents of history, nothing can be taken for granted. Not least the telling of a life.” (Stuart Hall 2017, 95)

Nothing can be taken for granted. Is not the space of the refugee camp in and of itself a spatialization of a political demand? It is a space of waiting for an eventual return. And in that space of waiting lies the everyday politics—what Hall termed the “social transactions of everyday colonial life” (Hall 2017, 93). Nothing can be taken for granted when the street you live on is named after a village you have always imagined but never visited. When the entrance to the camp is controlled by checkpoints meticulously designed as life valves. When the Gush Etzion settlements lie at the hilltop, vividly lit up and ferociously surrounded by barbed wires, surveillance cameras, and watch towers. Palestinian novelist, Hussein Barghouthi (2022), once described the settlement as “if hanging from space, perhaps because of the lighting too, without touching the ground, or history, yet.”[2] This is the ‘colonial sector’ as Fanon (2004, 4), writing on colonial Algeria, once dubbed it: “it is a sector of lights and paved roads, where the trash cans constantly overflow with strange and wonderful garbage, undreamed-of leftovers.”

Al ‘Arub is a refugee camp in northern Hebron in the West Bank. It houses ten thousand Palestinian refugees mostly displaced from villages nearing Gaza and Hebron after the establishment of Israel in 1948. The camp is surrounded by settlements—Gush Etzion to the north, Karmei Tzur to the south, and another, recent settler outpost to the north. To its north and northwest, the camp is fully engulfed by the 60-Route (see Figure 3), a highway built by Israel and shared—though with differentiated access—between Palestinians and the Israeli settlers. The most recent settler outpost was imposed atop a historic hospital (see Figure 4) built under Jordanian rule in the 1950s. In 2015, settlers moved into the building, kicking out the Palestinian family guarding it. They have since turned it into a wedding hall that was officially conjoined with the Gush Etzion Municipality in 2016. Stealing this building meant the gradual seizure of the land surrounding it. The road, cutting nearby the hospital before ascending towards the southern hill, continues this erasure; its completion was contingent on the seizure of Palestinian lands. Roads, as Salamanca (2020) argues, are part of a wider project of dispossession that serves the long-term domination of the settlers.

The colonial relations serve as the inherited background field within which capitalist, patriarchal, and racist relations converge to create, sustain, and perpetuate a settler way of life. But these relations as well as their convergence are historically contingent. This is the ‘historical premise’ that Hall (2021, 217) always insisted on: the forms of historical relations and their convergence with one another cannot be schematized a priori, for they are historically and geographically specific. “And, that this, in turn, requires attention to class-race (and other) articulations forged through situated practices in the multiple arenas of daily life” (Hart 2002, 31). So, what is the historical context in which dispossession takes place around a refugee camp in the West Bank in the current moment?

The current historical conjuncture in the West Bank is defined by a particular articulation (i.e., linking) between colonial and capitalist modes of accumulation, crosscut by gender, race, and class. In 1985, the Israeli state issued the Economic Stabilization Plan (ESP), which effectively neoliberalized the Israeli economy. The plan meant more intensified privatization of publicly-owned lands and companies, and further plugging of the Israeli economy into global circuits of capital (see Sa’di-Ibraheem 2021; Karkabi 2018). In 1993, the Oslo Accords were signed between the Palestinian Liberation Organization and the Israeli state, officially establishing the Palestinian Authority as a self-ruling government in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. The Accords were followed with the Protocol on Economic Relations (also called the Paris Protocol) in 1994, which integrated the Palestinian economy into Israel’s through a ‘customs union.’ Not only are the entry and exit ports controlled by the settler state, but also the inflow of international aid and the entire land of the West Bank (even when it is juridically categorized as areas A, B, and C with different levels of Israeli control). Both the Accords and the Protocol were supposed to be temporary until the final negotiations. However, they remain in effect until today.

Through those agreements, the Palestinian economy is locked in a relation of dependency. Adam Hanieh (2003, 18) argues that the Oslo Accords have aimed to outsource the costs of the military occupation to international aid and cantonize Palestinian geography. Writing on housing and the reconfiguration of Palestinian space in the post-Oslo conjuncture, Rabie’ (2021) argues that the accords became a way of managing and sustaining the inequality between the Israeli and Palestinian economies. The neoliberalization of the Israeli economy and the Oslo Accords set in motion a new coupling of capital and colonial relations, whereby the former comes to play a more direct role in dispossession. That coupling is mediated through multiple levels of determination: it triggers changes in the political, cultural, economic, and social spheres.

This brief mapping of the set of economic, political, and social relations that define the post-Oslo conjuncture already points to economic systems that stand within relations of domination and subordination. Writing on South Africa, Hall (2021, 229) proposes that the inequalities between different economies imply the existence of multiple forms of political representation. In the post-Oslo conjuncture, there exists a hierarchy of representation that reaches the entire map of historic Palestine. Palestinians living within the ’48 territories (such as Haifa) are positioned as citizens of the Israeli state. In contrast, Palestinians living within the ’67 territories are subjects of martial and administrative law. Israeli civil law too, as Rabie’ (2021) argues, is weaponized to entrench colonial hierarchies and domination. While the Palestinian Authority was meant to operate across the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, a political split occurred between Fatah (a secular, nationalist party) and Hamas (an Islamist party) after the 2006 Palestinian Legislative Council elections. Though internationally monitored, the elections’ results were rejected by the European Union, Israel, and the United States. While Hamas came to control the Gaza Strip, the Palestinian Authority (ruled by Fatah) came to control the West Bank.

The international delegitimization of Palestinian electoral politics meant more entrenched neoliberalization of the Palestinian economy. Neoliberalism aims to lower the barriers of trade and smoothen out the pathways for capital circulation while entrenching political, economic, and social inequalities. It is a general global phenomenon, but it actually exists as a historically determined phenomenon. Writing on post-Apartheid moment in South Africa, Hart (2002, 33) notes how the African National Congress led by Thabo Mbeki tried to balance the advancing of neoliberal agenda with liberation symbols and ideas. The Palestinian Authority embodies a similar conundrum. It mobilises a history of armed resistance to advance a neoliberal agenda that further entrenches colonial hierarchies. Such agenda have nurtured a Palestinian capitalist class, a Palestinian capitalism that exploits, rather than resists, the contradictions of the colonial reality. The Palestinian Authority led by Mahmoud Abbas, the head of the Palestinian Authority since 2005, has witnessed a noticeable harmonization between the Authority’s structures and the Israeli settler colonial state. In effect, this has meant close security coordination with the settler state, economic cooperation that selectively benefits a Palestinian bourgeoisie while impoverishing the rest, and intensified suppression of dissent.

Fanon (2004, 24) notes that compromise is the nationalist bourgeoisie’s attempt to reassure themselves and the colonists not to jeopardize everything. As Glen Coulthard (2014) notes, settler colonies revert to a ‘colonial politics of recognition,’ which aims to incorporate, and therefore annul, indigenous demands for self-determination through legal circuits that only serve the long-term dominance of the settlers. The result of this compromise in the West Bank has meant a hollowing of Palestinian institutional politics, a professionalization of grassroots politics through NGOization (see Hamammi 1995), and a proliferation of consumerist and indebted subjects enduring a military occupation while being tied by loans. This is the impossible promise of Oslo: to consume and dream of a better life within the structural constraints of a settler colonialism insistent on eliminating you from the land.

The camp in the West Bank is a constant reminder that dispossession remains active and constitutive across Palestine. That the settlement has eaten up the fabric around the refugee camp is an eloquent reminder that dispossession did not stop in 1948. But that does not mean dispossession has unfolded since then unabatedly, in the same shape and manner. The neoliberalization of the Israeli economy, followed by the Oslo Accords, demonstrates how capital and dispossession “adapt themselves to the contemporary imperatives of colonial domination” (Bhandar 2018, 14), ushering in new mechanisms of control, management, and erasure. In the post-Oslo conjuncture, dispossession continues but through new mechanisms, delivering a ‘transformed settler colonialism.’[3] Given their contingency, such mechanisms may be transformed, subverted, resisted, worked upon, or overthrown.

2. The village

“It’s difficult, too, to work through the question of how these pasts inhabit the historical present. Via many disjunctures—filaments which are broken, mediated, subterranean, unconscious—the dislocated presence of this history militates against our understanding of our own historical moment” (Hall 2017, 71).

The Israeli state was established through an event of dispossession that turned more than 750,000 Palestinians into refugees. At that time, the newly established state organized committees, institutions, and processes to turn such an event into a sustainable juridical, political, cultural, and economic formation (see Robinson 2013). It also relied on Zionist institutions and agencies established prior to 1948, including the Histadrut (the General Organization of Workers in Israel; see Zureik 1979). Between 1948 and 1953 in particular, the state experimented with multiple ad hoc processes to institutionalize the theft of Palestinian land and property. The efforts culminated in the establishment of the Custodian of Absentee Property, a governmental agency responsible for handling stolen buildings and lands. That period also witnessed the establishment of Amidar National Housing Company in 1949 and the Development Authority in 1951.

Using Stuart Hall’s (2021, 232) register, the bringing together of practices of dispossession into sustainable juridical institutions constitutes an act of “connotative condensation.” Settler colonialism is constituted by processes and practices that become linked in ways particular to each historical conjuncture. In the first two decades following the establishment of the settler state, it played a major role in organizing the shape and form of these processes and practices as well as the linkings (articulations) between them to maintain a system of domination that favours the long-term development of the settler.

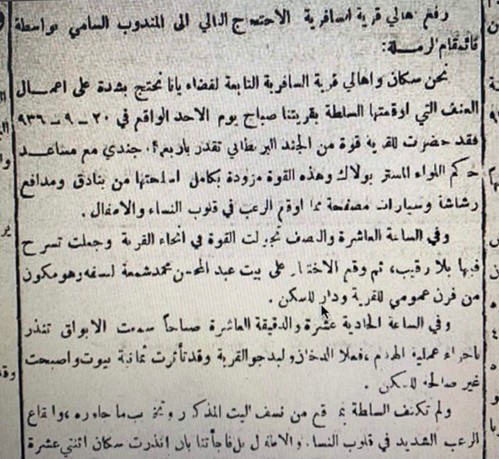

In 2018, my family and I enacted a rehearsal of return. Three generations (my grandmother, my father, and I) went through an Israeli checkpoint near Bethlehem. The fragmentation of Palestinian geographies means restrictions on the right to movement for Palestinians, so that the 60-Route, for example, is lived through different maps: one for settlers, and another for Palestinians. We arrived to al Safiriyya, which was once a Palestinian village ten kilometres to the east of Yafa (Jaffa). My grandparents owned a bakery here. And that bakery was demolished in 1937 by the British colonial forces as a punitive measure against the family’s participation in the Palestinian Great Revolt of 1936-39. When looking through Palestinian newspapers predating 1948, I found a call from the people of al Safiriyya in al Difa’ Newspaper, denouncing the demolition of Abdulmosen Abushama’s (my grandfather) house and bakery. If memory is “a means by which history is lived” (Hall 2017, 78), it is also a means by which space is reimagined and relived. This was my grandmother’s first visit back to al Safiriyya since 1948.

Many Palestinians I know attempted such a return: a necessary rehearsal that breaks the heart and reorients return towards the future. Return, then, becomes a constant process and practice of questioning the interlocking relations that structure dispossession as well as of weaving together the moments, acts, and movements of resistance against it.

The dispossession that had occurred in al Saifiryya, alongside another 450 Palestinian villages and the cities, serves as the event of condensation. The theft of property, and its articulation to economic and political institutions, was meant to create the settler subject as property-owning and the native Palestinian as propertyless. When discussing juridical forms and property under slavery, Hall (2021, 235) suggested that it was not just attitudes of racial superiority that precipitated slavery. Slavery, too, “produced those forms of juridical racism which distinguish the epoch of plantation slavery.” Again, this is an analysis that starts with ‘concrete historical work’ of a particular structure, asking: “what are the specific conditions which make [a particular] form of distinction socially pertinent, historically active?” (236)

It is the Zionist ideology, vouched in terra nullius logics of conquest that selectively repurpose secular and religious ideas to serve the particular social group of European settlers, that activates a constitutive distinction between the settler and the native. The state is a site of cohesion, the result of tendential articulations (particular, favoured linking) between ideology, subjectivity, and property. The state played the primary role in the erasure of al Safiriyya. Is not the erasure of al Safiriyya a primitive accumulation, an accumulation by dispossession, where the State and ideology (not only the economy, as Harvey (2004) might put it) play a primary role? As afterlives of that violence, the residents in al ‘Arub refugee camp experience violence differently in the post-Oslo historical conjuncture: violence mediated through the Israeli army as an agent of the state, the settler as an agent of Israeli civil law, and the Palestinian Authority as a native agency aimed at nurturing bourgeois interests while suppressing anti-colonial and social dissent. Settler colonialism is contingent on these historically determined practices and processes. And it is vulnerable to the rehearsals of return.

3. The city

On a cold day in January 2020, we drove around the city of Haifa.[4] We first went to Wadi Salib, which stands in the eastern part of the city with old homes—some neglected, others renovated—that belonged to Palestinian refugees before 1948. In al Burj neighbourhood stood the houses of Abdellatif Kanafani and Abed Elrahman El Haj (mayor of Haifa, 1870-1946). The house of the Kanafanis (Figure 7)—appropriated by the Israeli state in 1948, sold to the state-owned housing company Amidar in 1953 and then to four real estate companies in recent years (Sa’di-Ibraheem 2021, 698)—has been renovated and turned into law offices. The old and partially destroyed shops below the houses had a large poster in Hebrew by Ilan Pivko architects, showing the vision for their renovation. The old fronts would be polished and renovated, and atop of them, large ‘modern’ residential places would be built. These are all part of market-led, municipality-facilitated efforts to reshape what remains of Haifa.

Wadi Salib is a site of layered dispossession. The Israeli state forcibly drove out the Palestinian residents of the neighbourhood in 1948. While all the remaining Palestinians in Haifa were relocated to Wadi Nisnas neighbourhood and placed under strict military rule, arriving Arab Jews were placed in the Palestinian vacant homes. The Arab Jews were racialised as natural proprietors of these places as they were presumed to come from similar ‘mellah’[5] living conditions in Morocco (Weiss 2011). The racial hierarchy of the newly-established Israeli state was already being woven and mediated through space. The unbearable living conditions resulted in an Arab Jewish rebellion in 1959, leading to the evacuation of the neighbourhood (Shohat 2017, 72).

Contemporary attempts by the Haifa municipality and Israeli and international capital to refashion the neighbourhood as authentic real estate not only rely on but also perpetuate this layering of dispossession: firstly of the Palestinians, and secondly of the Arab Jews. The tendential articulation solidified in 1948, which favoured the white European settler as the archetypical proprietor of stolen Palestinian property, was accompanied by a sedimentation of other articulations, including the dispossession of the Palestinians and the racialization and precarization of the Arab Jew. The gradual, neoliberal refashioning of space within the ’48 territories, including Haifa, since 1985, occurs within the parameters of this inherited background field of colonial relations.

Indeed, as Milner (2020) shows in her discussion of the Arab Jewish Giv’at-Amal neighbourhood, built atop the depopulated Palestinian village of Jamassin in 1948, private capital feeds on this layering of dispossession by completely denying Palestinian claims to the land as well as contesting the precarious Arab Jewish settler’s title to it. Though included in the settler society as Jews whose religious lineage entitles them to a ‘right of return’ to stolen Palestinian lands (as per the 1950 Law of Return), Arab Jews are racialized as lesser settlers whose entitlement to the land is questioned. It is no surprise, then, that in 1986 the land of Jamassin-Giv’at Amal—along with the right to evict its Arab Jewish residents—was sold to several private entrepreneurs. Some of the Arab Jewish settlers, Milner tells us, weaponize their settler subjectivity and their participation in the dispossession of the Palestinians in order to substantiate their claim to the land. Capital, and its coupling with the colonial relations, constitute historical relations that are crosscut by race.

If, following Massey (2000) and Ajl et al (2015), we view the city as a condensed vantage point into articulated practices and processes (i.e., not a thing that precedes the process), the city becomes one socio-spatial form amongst many other possible and imagined ones. Furthermore, the city is a constellation of power relations determined by the particular historical conjuncture under examination. In the post-Oslo conjuncture, Palestinians living in Haifa face a new coupling of capital and colonial dispossession, crosscut by race, gender, and class, whereby capital takes a more primary role while feeding on the raw contradictions unleashed by the colonial relations. Although Palestinians within the ’48 territories are included as citizen subjects of the state, that inclusion is structured as an exclusion that remains reliant on a layering of dispossession that denies the Palestinian right to self-determination across the map.

Conclusion

I write at a time of turmoil and intensified, genocidal violence. Thus far, Israel has killed more than fifteen thousand Palestinians in the Gaza Strip. Israeli airstrikes have targeted hospitals and schools, erasing entire neighbourhoods. Entire Palestinian families have been wiped out of the civil registry. Israeli officials have waved the idea of the permanent displacement of Gazans to the Sinai desert. While Western media outlets and political establishments rush to obscure this as rational self-defence, taking a historicist and geographic approach to Gaza shows how Israel’s targeting of the Strip is a brutal manifestation of the settler colonial intent to eliminate the native Palestinians. This is the same intent that takes the shape of settlers and military watch towers in the West Bank and that targets what remains of Palestinian urbanity in Haifa through urban renewal projects. In Gaza, this intent takes the shape of a brutal siege that has been imposed since 2007, followed by a series of wars that aim at de-developing the Strip (see Roy 1995). When viewed from al ‘Arub refugee camp, al Safiriyya, Jamassin, and Haifa, it becomes clear that the Gaza Strip faces another layering of dispossession. Gaza lies at the bottom of a hierarchy of life and violence that Israel imposes across the map of historic Palestine.

Settler colonialism is a whole constituted by historically determined parts—parts that are, in turn, constituted by a historically determined whole (see Hart 2018, 375-376). And so is capitalism. The local, such as al ‘Arub camp, is not a mere unilateral manifestation reflective of an all-encompassing global process. It is a nodal point of articulation—specific, differentiated, contingent. This is Hall’s (1986) Marxism without guarantees: there is no guaranteed correspondence or noncorrespondence between the different levels of a social formation; structures do not pre-date relations; and the global process of capitalist accumulation and that of Israeli settler colonialism take differentiated iterations that rely on the relations constituting each spatio-historical conjuncture.

As such processes unfold across the map of Palestine, they take particular shapes and forms, resulting in various historically determined settler colonial paradigms: the military occupation in the West Bank, the besiegement, de-development, and targeting of human life in the Gaza Strip, the administrative law in Jerusalem, and the inclusion through exclusion in the ’48 territories. This is a map without guarantees: there is neither a guarantee that settler colonialism’s intent to eliminate the Palestinians will succeed, nor a guarantee that Palestinians will take up a particular form of resistance. This is a map without guarantees: it is a map that takes very seriously the structural constraints shaping the fragmented Palestinian geographies but also one that animates the pressures that Palestinian practices and modes of resistance exert on such historical forces. This is a map without guarantees, where settler colonialism may, one day, cease to exist. A map without guarantees, where rehearsals of return will, one day, cease to be rehearsals.

About the author

Hashem Abushama is a Departmental Lecturer and Career Development Fellow at St John’s College and the School of Geography and the Environment (SoGE) at the University of Oxford. He is a human geographer with interests in urban studies, cultural studies, critical development studies, and postcolonial geographies. He holds a DPhil in Human Geography from the School of Geography and the Environment and an MSc in Refugee and Forced Migration Studies from the Department of International Development at the University of Oxford, and a BA in Peace and Global Studies from Earlham College in the United States. His PhD dissertation won the runner up for the Leigh Douglas Memorial Award for the Best Dissertation in British Middle East Studies. His forthcoming monograph looks at settler colonialism, capitalism, dispossession, and arts in contemporary Palestine. His writings have appeared in Refuge: Canada’s Journal on Refugees, the Jerusalem Quarterly, Jadaliyya, and Palestine Square.

Footnotes

[1] I am here paraphrasing Stuart Hall’s (1986) powerful essay ‘The Problem of Ideology—Marxism without guarantees,’ where he criticizes orthodox Marxism’s tendency to presume a necessary correspondence between the different levels of social formations. He argues that presuming a functionalist understanding whereby, for example, those occupying a working-class subjectivity are presumed to be revolutionary by virtue of that subjectivity leads to a determinism that deadens politics. There are no guarantees that such a subjectivity will be revolutionary for that depends on the actual, concrete struggles.

[2] Translated from Arabic by the author.

[3] Here, I am extending Stuart Hall’s concept of ‘transformed racisms’ (see Hall 2021). I explore this in greater length in an article titled ‘Articulations: a relational comparison of settler colonial dispossession and cultural practices in Haifa and Ramallah’ submitted to the Annals of the American Association of Geographers Journal.

[4] That day, I was taken on a tour around Haifa by Palestinian geographer Yara Sa’di-Ibraheem and her partner, Hisham, whom I would like to thank for their knowledge and time.

[5] Mellah is an Arabic term that refers to Jewish neighbourhoods in Morocco.

Bibliography

Ajl, Max, Hillary Angelo, Neil Brenner, Neil Brenner, John Friedmann, Matthew Gandy, Brendan Gleeson, et al. 2015. Implosions /Explosions: Towards a Study of Planetary Urbanization. Berlin: JOVIS Verlag GmbH. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783868598933

Barghouthi, Hussein. 2022. Among the Almond Trees: A Palestinian Memoir. Translated by Ibrahim Muhawi With an Introduction by Ibrahim Muhawi. The Arab List. Seagull Books. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/distributed/A/bo124470392.html.

Bhandar, Brenna. 2018. Colonial Lives of Property: Law, Land, and Racial Regimes of Ownership. Global and Insurgent Legalities. Durham [North Carolina: Durham North Carolina : Duke University Press.

Coulthard, Glen Sean. 2014. Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition. Indigenous Americas. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

‘Difa’ Newspaper 1937’. n.d. Accessed 6 November 2023. https://www.nli.org.il/ar/newspapers/difaa/1936/09/23/01/.

Estes, Nick. 2019. Our History Is the Future: Standing Rock versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance. London ; Verso.

Fanon, Frantz. 2004. The Wretched of the Earth: Frantz Fanon ; Translated from the French by Richard Philcox ; with Commentary by Jean-Paul Sartre and Homi K. Bhabha. New York: Grove Press.

Hall, Stuart. 1986. ‘The Problem of Ideology-Marxism without Guarantees’. The Journal of Communication Inquiry 10 (2): 28–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/019685998601000203.

———. 2017. Familiar Stranger: A Life between Two Islands. London: Allen Lane.

———. 2021a. Selected Writings on Race and Difference. Durham: Duke University Press.

———. 2021b. ‘Race, Articulation and Societies Structured in Dominance [1980]’. In Selected Writings on Race and Difference, edited by Paul Gilroy and Ruth Wilson Gilmore, 0. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9781478021223-014.

Hammami, Rema. 1995. ‘NGOs: The Professionalisation of Politics’. Race & Class 37 (2): 51–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/030639689503700200.

Hanieh, Adam. 2003. ‘From State-Led Growth to Globalization: The Evolution of Israeli Capitalism’. Journal of Palestine Studies 32 (4): 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1525/jps.2003.32.4.5.

———. 2013. Lineages of Revolt: Issues of Contemporary Capitalism in the Middle East. Chicago, Illinois: Haymarket Books.

Harker, Christopher. 2020. Spacing Debt: Obligations, Violence, and Endurance in Ramallah, Palestine [Electronic Resource]. Durham: Duke University Press. https://ezproxy-prd.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/login?url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1215/9781478012474.

Hart, Gillian. 2018. ‘Relational Comparison Revisited: Marxist Postcolonial Geographies in Practice’. Progress in Human Geography 42 (3): 371–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516681388.

Hart, Gillian Patricia. 2002. Disabling Globalization: Places of Power in Post-Apartheid South Africa. Berkeley: University of California Press. http://bvbr.bib-bvb.de:8991/F?func=service&doc_library=BVB01&local_base=BVB01&doc_number=009887163&line_number=0001&func_code=DB_RECORDS&service_type=MEDIA.

Harvey, David. 2004. ‘The “New” Imperialism: Accumulation by Dispossession’. Socialist Register 40.

Karkabi, Nadeem. 2018. ‘How and Why Haifa Has Become the “Palestinian Cultural Capital” in Israel’. City & Community 17 (4): pp1168-1188. https://doi.org/10.1111/cico.12341.

Levien, Michael. 2015. ‘From Primitive Accumulation to Regimes of Dispossession: Six Theses on India’s Land Question’. Economic and Political Weekly 50 (22): 146–57.

Massey, Doreen. 2000. ‘Travelling Thoughts’. In Without Guarantees: In Honour of Stuart Hall, edited by Stuart Hall, Paul Gilroy, Lawrence Grossberg, and Angela McRobbie, 225–32. London: Verso.

Massey, Doreen B. 2005. For Space. London: SAGE.

Milner, Elya Lucy. 2020. ‘Devaluation, Erasure and Replacement: Urban Frontiers and the Reproduction of Settler Colonial Urbanism in Tel Aviv’. Environment and Planning. D, Society & Space 38 (2): 267–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775819866834.

Rabie, Kareem. 2021. Palestine Is Throwing a Party and the Whole World Is Invited: Capital and State Building in the West Bank [Electronic Resource]. E-Duke Books Scholarly Collection. Durham: Duke University Press. https://ezproxy-prd.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/login?url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1215/9781478021407.

Robinson, Shira. 2013. Citizen Strangers: Palestinians and the Birth of Israel’s Liberal Settler State. Stanford Studies in Middle Eastern and Islamic Societies and Cultures. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

Roy, Sara M. 1995. The Gaza Strip: The Political Economy of de-Development. Washington, D.C: Institute for Palestine studies.

Sa’di-Ibraheem, Yara. 2021. ‘Privatizing the Production of Settler Colonial Landscapes: “Authenticity” and Imaginative Geography in Wadi Al-Salib, Haifa’. Environment and Planning. C, Politics and Space 39 (4): 686–704. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654420946757.

SALAMANCA, OMAR JABARY. 2016. ‘Assembling the Fabric of Life: When Settler Colonialism Becomes Development’. Journal of Palestine Studies 45 (4): 64–80. https://doi.org/10.1525/jps.2016.45.4.64.

Salamanca, Omar Jabary, Mezna Qato, Kareem Rabie, and Sobhi Samour. 2012. ‘Past Is Present: Settler Colonialism in Palestine’. Settler Colonial Studies 2 (1): 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/2201473X.2012.10648823.

Shohat, Ella. 2017. On the Arab-Jew, Palestine, and Other Displacements: Selected Writings. London: Pluto Press.

Weiss, Yfaat. 2011. A Confiscated Memory: Wadi Salib and Haifa’s Lost Heritage. New York: Columbia University Press.

Wolfe, Patrick. 2006. ‘Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native’. Journal of Genocide Research 8 (4): 387–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623520601056240.

Zureik, Elia. 1979. The Palestinians in Israel: A Study in Internal Colonialism. International Library of Sociology. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

The Stuart Hall Foundation welcomed renowned public intellectual Jacqueline Rose for our 6th Annual Stuart Hall Public Conversation at Conway Hall, London, on Saturday 11th February 2023. She delivered a lecture entitled ‘What is a Subject? Politics and Psyche After Stuart Hall’. Stuart Hall’s work can be read as a perpetual searching, however difficult or painful, for the linchpins which entangle intimate personal history to global political relations. It’s through this approach to reading Hall that Rose began to realise how deeply embedded his work was within psychoanalytical thought. In this lecture, Rose tracks the key aspects of Hall’s thinking, and questions how, through its prism, he might have reached out to some of the most anguished political and cultural realities of our current times. Following Rose’s keynote and a brief intermission, she is joined by psychotherapist Sharon Numa in conversation. Jacqueline Rose recently adapted this lecture into an essay on Stuart Hall at The New York Review. Read it here: https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2023/09/21/the-analyst-stuart-hall-jacqueline-rose/The Stuart Hall Foundation’s Annual Autumn Keynote with Arundhati Roy, September 2022. In the twenty-five years since the release of her world-renowned Booker Prize winning novel, The God of Small Things (1997), Arundhati Roy has consistently interrogated the meaning of justice in all its complexity, social, economic and ecological. Her last novel was The Ministry of Utmost Happiness (2017) which has been translated into more than 40 languages. Her latest collection of essays is Azadi: Freedom, Fascism, and Fiction in the Age of the Virus (2020). As we endure an unprecedented global pandemic, governmental inaction in response to the climate crisis, and the intensification of authoritarian practices across the global north and south alike, Arundhati Roy reflects on how we have arrived at this conjuncture and what might come next. In her keynote titled ‘Things That Can and Cannot Be Said: The dismantling of the world as we knew it’, Roy discusses the local and global dimensions of these crises and the ongoing resistance to them. Roy is then joined in conversation with Farzana Khan, Executive Director and Co-founder of Healing Justice London, and responds to questions from the audience.In the final episode of Living Archives, Alberta Whittle and Sekai Machache think together about freedom, urgency and slowness, their many transnational and international collaborations, and their feelings about edges.

Conversation transcript available here. Listen to more episodes here.

Living Archives is an oral histories project co-produced by the Stuart Hall Foundation and the International Curators Forum. The project is made up of six intergenerational conversations. Each conversation considers an alternative history of contemporary Britain through the testimony of UK-based diasporic artists working between the 1980s and the present-day. The project will form, what Stuart Hall calls, a “living archive of the diaspora” which maps the development, endurance, and centrality of diasporic artistic production in Britain.

Hosted by ICF’s Deputy Artistic Director, Jessica Taylor, practitioners reflected on the reasons they became artists, the development of their practices, the different moments and movements they bore witness to, and the beautiful reasons they chose to be in conversation with each other.

Hosted by Jessica Taylor

Edited by Chris Browne

Designs by Yolande Mutale

Music by LOX

Bios

Alberta Whittle is an artist, researcher, and curator. She was awarded a Turner Bursary, the Frieze Artist Award, and a Henry Moore Foundation Artist Award in 2020. Alberta is a PhD candidate at Edinburgh College of Art and is a Research Associate at The University of Johannesburg. She was a RAW Academie Fellow at RAW Material in Dakar in 2018 and is the Margaret Tait Award winner for 2018/9.

Her creative practice is motivated by the desire to manifest self-compassion and collective care as key methods in battling anti-blackness. She choreographs interactive installations, using film, sculpture, and performance as site-specific artworks in public and private spaces.

Alberta has exhibited and performed in various solo and group shows, including at Jupiter Artland (2021), Gothenburg Biennale (2021), The Lisson Gallery (2021), MIMA (2021), Viborg Kunstal (2021), Remai Modern (2021), Liverpool Biennale (2021), Art Night London (2021), The British Art Show – Aberdeen (2021), Glasgow International (2021), Glasgow International (2020), Grand Union (2020), Eastside Projects (2020), DCA (2019), GoMA, Glasgow (2019), Pig Rock Bothy at the National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh (2019), 13th Havana Biennale, Cuba (2019), The Tyburn Gallery, London (2019), The City Arts Centre, Edinburgh (2019), The Showroom, London (2018), National Art Gallery of the Bahamas (2018), RAW Material, Dakar (2018), FADA Gallery, Johannesburg (2018), the Apartheid Museum, Johannesburg (2017), FRAMER FRAMED, Amsterdam (2015), Goethe On Main, Johannesburg (2015), at the Johannesburg Pavilion at the 56th Venice Biennale, Venice (2015), and BOZAR, Brussels (2014), amongst others.

Her work has been acquired for the UK National Collections, The Scottish National Gallery Collections, Glasgow Museums Collections and The Contemporary Art Research Collection at Edinburgh College of Art amongst other private collections.

Alberta is representing Scotland at the 59th Venice Biennale in 2022. And over 2021, Alberta will be sharing new work as part of the British Art Show 9, RESET at Jupiter Artland, Right of Admission at the University of Johannesburg, Art from Britain and The Caribbean at Tate Modern, Sex Ecologies at Kunstal Trondheim, Norway, In The Castle Of My Skin (MIMA) and Gothenburg Biennale (2021).

Alberta’s writing has been published in MAP magazine, Visual Culture in Britain, Visual Studies, Art South Africa and Critical Arts Academic Journal.

Sekai Machache (she/they) is a Zimbabwean-Scottish visual artist and curator based in Glasgow, Scotland. Her work is a deep interrogation of the notion of self, in which photography plays a crucial role in supporting an exploration of the historical and cultural imaginary.

Aspects of her photographic practice are formulated through digital studio-based compositions utilising body paint and muted lighting to create images that appear to emerge from darkness.

In recent works she expands to incorporate other media and approaches that can help to evoke that which is invisible and undocumented. She is interested in the relationship between spirituality, dreaming and the role of the artist in disseminating symbolic imagery to provide a space for healing against contexts of colonialism and loss.

Sekai is the recipient of the 2020 RSA Morton Award and is an artist in residence with the Talbot Rice Residency Programme 2021-2023.

Sekai works internationally and often collaboratively, for and with her community and is a founding and organising member of theYon Afro Collective (YAC).

Produced with funding from the Centre on the Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE) and Arts Council England.

For the fifth episode of Living Archives, Joy Gregory and Anthea Hamilton share the ways their experiences have influenced their practice, the relationship between education and art-making and what plant life can teach us about being in the world.

Conversation transcript available here. Listen to more episodes here.

Living Archives is an oral histories project co-produced by the Stuart Hall Foundation and the International Curators Forum. The project is made up of six intergenerational conversations. Each conversation considers an alternative history of contemporary Britain through the testimony of UK-based diasporic artists working between the 1980s and the present-day. The project will form, what Stuart Hall calls, a “living archive of the diaspora” which maps the development, endurance, and centrality of diasporic artistic production in Britain.

Hosted by ICF’s Deputy Artistic Director, Jessica Taylor, practitioners reflected on the reasons they became artists, the development of their practices, the different moments and movements they bore witness to, and the beautiful reasons they chose to be in conversation with each other.

Hosted by Jessica Taylor

Edited by Chris Browne

Designs by Yolande Mutale

Music by LOX

Bios

Born in 1978 in London, Anthea Hamilton is a British artist known for creating large-scale installations and surreal artworks. She graduated from Leeds Metropolitan University in 2000 and the Royal College of Art, London, in 2005. Her practice encompasses film, installation, performance, and sculpture, and her work is frequently site-specific. Hamilton’s approach combines archival study, popular culture, and scientific research with resonant images and objects in unusual and surreal ways. Her installations engage visitors with imagined narratives that incorporate references from art, cinema, design, and fashion. Conversation and collaboration are also key to the way she works. In 2016 Hamilton was short-listed for the Turner Prize for Project for Door (2015). In 2017 she became the first Black woman to be awarded a commission to create a work for Tate Britain’s Duveen Galleries.

Joy Gregory is a graduate of Manchester Polytechnic and the Royal College of Art. She has developed a practice which is concerned with social and political issues with particular reference to history and cultural differences in contemporary society.

As a photographer she makes full use of the media from video, digital and analogue photography to Victorian print processes. In 2002, Gregory received the NESTA Fellowship, which enabled her the time and the freedom to research for a major piece around language endangerment. The first of this series was the video piece Gomera, which premiered at the Sydney Biennale in May 2010.

She is the recipient of numerous awards and has exhibited all over the world showing in many festivals and biennales. Her work included in many collections including the UK Arts Council Collection, Victoria and Albert Museum, Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane, Australia, and Yale British Art Collection. She currently lives and works in London.

Produced with funding from the Centre on the Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE) and Arts Council England.

In episode 4 of Living Archives, Ajamu and Bernice Mulenga bend time reflecting on their respective approaches to photography, intimacy and working with large institutions.

Conversation transcript available here. Listen to more episodes here.

Living Archives is an oral histories project co-produced by the Stuart Hall Foundation and the International Curators Forum. The project is made up of six intergenerational conversations. Each conversation considers an alternative history of contemporary Britain through the testimony of UK-based diasporic artists working between the 1980s and the present-day. The project will form, what Stuart Hall calls, a “living archive of the diaspora” which maps the development, endurance, and centrality of diasporic artistic production in Britain.

Hosted by ICF’s Deputy Artistic Director, Jessica Taylor, practitioners reflected on the reasons they became artists, the development of their practices, the different moments and movements they bore witness to, and the beautiful reasons they chose to be in conversation with each other.

Hosted by Jessica Taylor

Edited by Chris Browne

Designs by Yolande Mutale

Music by LOX

Bios

Ajamu [Hon FRPS] is a fine art studio based / darkroom led photographic artist and scholar. His work has been shown in Museums, galleries and alternative spaces worldwide. In 2022, Ajamu was canonised by The Trans Pennine Travelling Sisters as the Patron Saint of Darkrooms and received and honorary fellowship from the Royal Photographic Society. Work appears in private abd public collections worldwide.

Bernice Mulenga is a British-Congolese photographer with a distinct aptitude for archiving, documenting and interrogating the world around them. Mulenga’s work centres on their community and the experiences within it—most notably in their ongoing photo series #friendsonfilm. Their work also explores reoccurring themes surrounding identity, sexuality, grief, darkness and family.

Produced with funding from the Centre on the Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE) and Arts Council England.

In the third episode of Living Archives, Roshini Kempadoo and Jacob V Joyce exchange ideas around Stuart Hall’s work and legacy, the relationship between the archive and artistic practice and finding allies in history.

Conversation transcript available here. Listen to more episodes here.

Living Archives is an oral histories project co-produced by the Stuart Hall Foundation and the International Curators Forum. The project is made up of six intergenerational conversations. Each conversation considers an alternative history of contemporary Britain through the testimony of UK-based diasporic artists working between the 1980s and the present-day. The project will form, what Stuart Hall calls, a “living archive of the diaspora” which maps the development, endurance, and centrality of diasporic artistic production in Britain.

Hosted by ICF’s Deputy Artistic Director, Jessica Taylor, practitioners reflected on the reasons they became artists, the development of their practices, the different moments and movements they bore witness to, and the beautiful reasons they chose to be in conversation with each other.

Hosted by Jessica Taylor

Edited by Chris Browne

Designs by Yolande Mutale

Music by LOX

Bios

Roshini Kempadoo is an international photographer, media artist and scholar with the School of Arts, University of Westminster. She has worked for over 30 years as a cultural activist and advocate, having been instrumental to the development of Autograph (ABP) and Ten.8 Photographic Magazine. As an artist she re-imagines everyday experiences and womens’ perspectives relating to Caribbean legacies and memories. Central to this is her book Creole in the Archive: Imagery, Presence and Location of the Caribbean Figure (2016). Her ongoing research develops creative methodologies on issues of race and extraction in relation to ecological futures.

Jacob V Joyce is an artist, researcher and educator from South London. Their work is community focussed ranging from mural painting, illustration, workshops, poetry and punk music with their band Screaming Toenail. Joyce has illustrated international human rights campaigns for Amnesty International and Global justice Now, had their comics published in national newspapers and self published a number of DIY zines. Their work with OPAL (Out Proud African LGBTI) has gone viral across the African Continent and increased the visibility of activists fighting the legacies of colonially instated homophobic legislation.

Joyce was recently awarded a Support Structures Fellowship from the Serpentine Gallery and a Westminster PhD research scholarship at C.R.E.A.M, (Centre for Research and Education in Art Media.) Previous recognitions include a collaborative residency at Serpentine Galleries Education Department with Rudy Loewe 2020, TFL (Transport For London) Public Arts Grant 2019, Artist Participation Residency at Gasworks London/East Yard Trinidad Tobago 2019, Tate Galleries Education Department Residency 2019, Nottingham Contemporary Community Artist Residency 2017.

Joyce is a non-binary artist amplifying historical and nourishing new queer and anti-colonial narratives.

Produced with funding from the Centre on the Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE) and Arts Council England.

In episode 2 of Living Archives Beverley Bennett and Marlene Smith discuss their practices in relation to family, collectivity and memory.

Conversation transcript available here. Listen to more episodes here.

Living Archives is an oral histories project co-produced by the Stuart Hall Foundation and the International Curators Forum. The project is made up of six intergenerational conversations. Each conversation considers an alternative history of contemporary Britain through the testimony of UK-based diasporic artists working between the 1980s and the present-day. The project will form, what Stuart Hall calls, a “living archive of the diaspora” which maps the development, endurance, and centrality of diasporic artistic production in Britain.

Hosted by ICF’s Deputy Artistic Director, Jessica Taylor, practitioners reflected on the reasons they became artists, the development of their practices, the different moments and movements they bore witness to, and the beautiful reasons they chose to be in conversation with each other.

Hosted by Jessica Taylor

Edited by Chris Browne

Designs by Yolande Mutale

Music by LOX

Bios

Beverley Bennett is an artist-filmmaker whose work revolves around the possibilities of drawing, performance and collaboration. Her practice is connected multiple ways of making. The first of these is a concern with the importance of ‘gatherings’ to denote a methodology that differs from the more hierarchical model of the workshop; one person leading and sharing information with participants taking part in the activities. Instead ‘gatherings’ are cyclical, whereby everyone learns from each other and often formulate in myriad ways, from reading together to gathering at a party. This has created a ‘tapestry of voices’, an interweaving of communalities and differences that provide a broader view, an important part of amplifying intergenerational relationships. The second is an investigation of the idea of The Archive (often beginning projects by creating / adding to her own extensive personal archives of interviews, using them for preliminary research and experimentation) and the third is collaboration. This is frequently through socially political work with other creatives, fine artists, community members, young children and their families. Her practice provides spaces for participants to become collaborators and provides a point of focus from where to unpick ideas around what constitutes an art practice and for whom art is generated.

Marlene Smith is a British artist and curator. She was a member of the Blk Art Group in the 1980s and is one of the founding members of the BLK Art Group Research Project. She was director of The Public in West Bromwich and UK Research Manager for Black Artists and Modernism, a collaborative research project run by the University of the Arts London and Middlesex University. She is Director of The Room Next to Mine, and was an Associate of Lubaina Himid’s Making Histories Visible Project and Associate Artist at Modern Art Oxford.

Selected exhibitions include: The More Things Change, Wolverhampton Art Gallery (2023); Cut & Mix, New Art Exchange, Nottingham (2022); Portals, East Side Projects, Birmingham (2021); Get Up, Stand Up, Now!Generations of Black Creative Pioneers, Somerset House, London (2019); The Place is Here,Nottingham Contemporary and South London Gallery (2017); Thinking Back: a montage of black art in Britain, Van Abbe Museu, Eindhoven, Netherlands (2016); Her work is in the Government Art collection and the collections of Sheffield museums and Wolverhampton art gallery.

Produced with funding from the Centre on the Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE) and Arts Council England.

In this, the first conversation in the Living Archives series, we sit down with Ingrid Pollard and Rudy Loewe to discuss the links between their practices, the relationship between activism and art-making and playful storytelling.

Conversation transcript available here. Listen to more episodes here.

Living Archives is an oral histories project co-produced by the Stuart Hall Foundation and the International Curators Forum. The project is made up of six intergenerational conversations. Each conversation considers an alternative history of contemporary Britain through the testimony of UK-based diasporic artists working between the 1980s and the present-day. The project will form, what Stuart Hall calls, a “living archive of the diaspora” which maps the development, endurance, and centrality of diasporic artistic production in Britain.

Hosted by ICF’s Deputy Artistic Director, Jessica Taylor, practitioners reflected on the reasons they became artists, the development of their practices, the different moments and movements they bore witness to, and the beautiful reasons they chose to be in conversation with each other.

Hosted by Jessica Taylor

Edited by Chris Browne

Designs by Yolande Mutale

Music by LOX

Bios

Ingrid Pollard is a photographer, media artist and researcher. She is a graduate of the London College of Printing, Derby University, with a Doctorate from University of Westminster Ingrid has developed a social practice concerned with representation, history and landscape with reference to race, difference and the materiality of lens based media. Her work is included in numerous collections including the UK Arts Council, Tate Britain and the Victoria & Albert Museum. She lives and works in Northumbria, UK.

–

Rudy Loewe (b. 1987) is an artist visualising black histories and social politics through painting, drawing and text. They began a Techne funded practice-based PhD at the University of the Arts London in 2021. This research critiques Britain’s role in suppressing Black Power in the English-speaking Caribbean, during the 60s and 70s. Loewe is creating paintings and drawings that unravel this history included in recently declassified Foreign & Commonwealth Office records. Their approach to painting speaks to their background in comics and illustration — combining text, image and sequential narrative.

Recent exhibitions include A Significant Threat, VITRINE Fitzrovia, London (2023); uMoya: the sacred return of lost things, Liverpool Biennial (2023); Unattributable Briefs: Act Two, Orleans House Gallery, London (2023); Unattributable Briefs: Act One, Staffordshire St., London (2022); New Contemporaries, Humber Street Gallery and South London Gallery (2022); Back to Earth, Serpentine Gallery, London (2022); and NAE Open 22, New Art Exchange, Nottingham (2022).

Produced with funding from the Centre on the Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE) and Arts Council England.

In the sixth and final episode of Locating Legacies, series host Gracie Mae Bradley speaks to Ruth Wilson Gilmore. Often dismissed or set aside as a US-based movement, Gracie and Ruth sit down together to explore how we can think about the histories, legacies and politics of abolition in the British context and beyond. They map how local instances of political organising express themselves globally, as well as interrogating how past struggles express themselves in the present.

Ruth Wilson Gilmore is the Director of the Center for Place, Culture, and Politics and professor of geography in Earth and Environmental Sciences and American Studies at the City University of New York. She is the co-founder of many grassroots organisations, including the California Prison Moratorium Project, Critical Resistance, and the Central California Environmental Justice Network. She is also the author of Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California, and Abolition Geography.

In the sixth and final episode of Locating Legacies, series host Gracie Mae Bradley speaks to Ruth Wilson Gilmore. Often dismissed or set aside as a US-based movement, Gracie and Ruth sit down together to explore how we can think about the histories, legacies and politics of abolition in the British context and beyond. They map how local instances of political organising express themselves globally, as well as interrogating how past struggles express themselves in the present.

Ruth Wilson Gilmore is the Director of the Center for Place, Culture, and Politics and professor of geography in Earth and Environmental Sciences and American Studies at the City University of New York. She is the co-founder of many grassroots organisations, including the California Prison Moratorium Project, Critical Resistance, and the Central California Environmental Justice Network. She is also the author of Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California, and Abolition Geography.

About the Series:

Locating Legacies is a fortnightly podcast created by the Stuart Hall Foundation, co-produced by Pluto Press and funded by Arts Council England. The series is dedicated to tracing the reverberations of history to contextualise present-day politics, deepen our understanding of some of the crucial issues of our time, and to draw connections between past struggles and our daily lives.

Get 40% off books in our ‘Locating Legacies’ reading list: plutobooks.com/locatinglegacies

This project was made possible through funding from Arts Council England.

_

Listen to more episodes here.

‘Part of The Furniture’ Stuart Hall Artist Residency

Pausing half-way through her artist residency at the Stuart Hall Library, Dharma Taylor shares with us a collection of her notes, which she describes as being ‘all over the place, but honest insights into the way this research has organically developed’. Through her writing, she is finding connections between text as a starting point, inspiration directly from the design world and then ultimately, the physical realisation of her work.

A Living Archive – Research Progress by Dharma Taylor

“Just relax into it and let one publication lead to another.”

The above quote came as reassurance from artist and designer Mac Collins after speaking to him on the phone from what sounded like his studio in Nottingham just before he showcased a new large-scale body of work at the British Pavilion for Venice Biennale 2023 titled ‘Dancing Before The Moon’ and just after he presented a new chair in Ronan Mckenzie’s group show ‘To Be Held’ in Margate.

I reached out to Mac as part of my research as the sixth artist in residence at the Stuart Hall Library. Mac and I have supported each other’s furniture narratives for the past few seasons, and I’ve always respected and related to him as a designer who works with wood as a material.